If a pioneer from Church Crookham had succeeded, Hampshire fields might have fewer solar panels and more tobacco plants.

For obvious reasons, smoking is today a minority activity, but a hundred years ago almost all men and many women smoked. Which led to plans between the wars to develop tobacco farming in north Hampshire as a mean of making use of poor agricultural land and boosting employment.

An arch-activist was Arthur Brandon of Church Crookham, described as “one of the great pioneers of the revival of tobacco growing”. The praise was heaped on him in 1952 by poet and self-sufficiency guru Ronald Duncan in a lecture given in London to the Royal Society of Arts.

He had taken up Brandon’s baton and boasted: “I am one of the pioneers of the revival of tobacco growing in this country and … in 1944, I obtained a Commercial Grower’s licence, being the first person in this country to do so.” In fact, he was not in any sense ‘commercial’, but was one of the estimated 100,000 amateurs in the country growing their own tobacco after WWII and thereby depriving the Treasury of an estimated £400,000 a year.

In his lecture he was looking back at Brandon’s hard-pressed efforts to make a profit of growing tobacco between 1911 and 1937 at Church Crookham, on either side of Redfields Lane, which joins the A287 to the village. He had spent his early life as a brewer in Putney, brewing ale, porter and stout, according to Kelly’s Directory of 1891.

In 1896, at the age of 40, although still running the brewery in London, he moved out and bought Redfields House, built in Church Crookham in 1879 for a barrister of the Inner Temple. It had a small estate of 148 acres, with meadows, woods, a trout stream and game coverts. Brandon added to it with land bought nearby and set out as a small-scale farmer, growing hops, corn and potatoes and rearing pigs.

In 1910, a grandly named Tobacco Growing Development Commission advised the government to lift the ban on tobacco growing in England which had been in force for 250 years – and Brandon seized the opportunity.

The reasons for such a long-standing ban are complex, but at the heart of it is taxation. Tobacco was first brought to England in 1550 by Sir John Hawkins, and to France by Jean Nicot (hence nicotine). Ever since, it has long been the subject of ‘roller-coaster’ politics.

In 1604, James I himself got involved, writing A Counterblaste to Tobacco and calling smoking “a custome lothsome to the eye, hatefull to the Nose, harmefull to the braine, [and] dangerous to the Lungs”. Popes excommunicated people for smoking and in Russia they were exiled to Siberia with horrible mutilations of the face. Had the Stuart king succeeded, the country might have benefited greatly, but the rewards of taxation were too great to be ignored, and so he made tobacco a royal monopoly with imports only allowed from Virginia.

Even so, pamphlets such as Advice how to plant tobacco in England abounded, declaring: “There is not so base a groome, that commes into an Alehouse to call for his pot, but must have his pipe of Tobacco”. And after the restoration of 1660, Charles II strengthened the monopoly and made tobacco growing in England a penal offence.

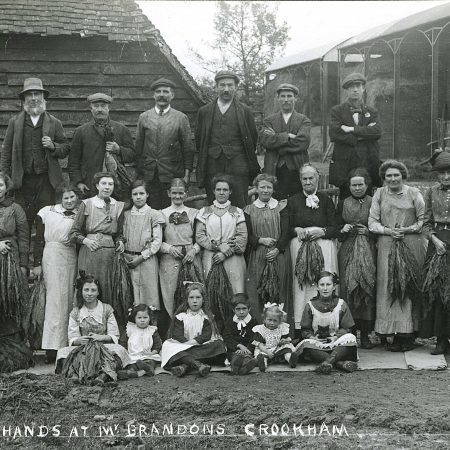

It was against this background that Arthur Brandon came into the picture. The story has been told by Phyllis Ralton, with the help of the Crondall Society, in her paper Mr Brandon’s Tobacco Farm, published by the Fleet and Crookham Local History Group. Its illustrations and many others are held in Winchester by the Hampshire Record Office (139A08; 195A08).

Initially the Development Commission recommended a rebate in excise duty for English growers, but in 1913 this was withdrawn on grounds of free trade and replaced by a grant to be administered by a newly formed British Tobacco Growers’ Association. However, little happened until after WWI, when in 1919 the government granted a preferential duty of one-sixth for Empire tobacco, which included England.

It was, however, a struggle for English growers to compete, due wages being lower overseas and labyrinthine red tape. And Brandon, who had become the President of the BTGA, was in the thick of it. Complaining about the problems, he wrote: “Even now I have to enter into a bond to grow, a bond to cure, a bond to receive tobacco, and a bond to send it away. The old laws are so obsolete that the authorities would not accept a leading bank as surety, but insisted on a bank of their own naming.”

In reality, the Treasury probably did not want to promote tobacco growing, preferring to collect duty on imports from outside the Empire. Arguments that it would enable poor land to be cultivated and swell employment fell on deaf ears.

Nonetheless, Brandon persevered with his land at Church Crookham. It was not easy: the business was complex, labour intensive and required considerable investment – for drying sheds, steam equipment and a press.

He certainly earned his ‘pioneer’ status, experimenting on his land with no fewer than 30 varieties of plant, settling eventually on Samos and Blue Pryor. Tobacco samples from his farm are in the collection of Farnham Museum. One advantage of growing tobacco is that the seeds are so small that nine plants are said to be enough to sow 20 acres!

Cultivation required not only weeding, which was done with horse-drawn and hand hoes, but also ‘topping’ to pinch out the terminal bud and promote leaf growth. Harvesting started in mid-August and went on until the end of September. The whole plant was required for pipe tobacco and for cigars, whereas leaves were used for cigar wrappers and cigarettes.

Next, in a process called ‘spearing’, the leaves were left to wilt in the sun, before being ‘cured’ with smoke from oak logs over a period of no less than six weeks. The leaves were stripped, graded for size and colour and bundled into ‘hands’, a process called ‘re-handling’. The hands were then dried in sheds with steam-heated radiators at 60℃ until an appropriate level of moisture had been reached.

Finally, the leaves were softened with steam and packed into large barrels, each holding about 1,000 lbs of tobacco.

It is hardly surprising that a form of farming that involved such a complex process and was hindered by onerous government regulations did not survive. Brandon, however, did not give up easily, and his battle with government taxation made him something of a media star for press and radio.

However, he did not make it to the small screen. In 1937 a call came to appear on television, but he was too ill to accept and his place was taken by his son-in-law and the farm manager. Later in the year, at the age of 81, he died, and commercial tobacco farming in England virtually died with him.

A PDF of Mr Brandon’s Tobacco Farm by Phyllis Ralton is available for £3.50 from: fclhg@talktalk.net.

Sources

R. Duncan, The history and present position of tobacco growing in England, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, 1952, vol. 100: 316-328.

A. Rive, A brief history of regulation and taxation of tobacco in England, The William and Mary Quarterly, 1929, vol. 9: 73-87.

Contributed by Barry Shurlock, first published in the Hampshire Chronicle, 27 May, 2021.