On 6 May 1623, King James I (& VI) granted a wine licence to John James of Southampton. The licence allowed John James to collect the rents from an inn called the Bugle, and also receive the customs from any wine retailed in the said inn. We know about this grant because of a case John James brought into the equity side of the Court of Exchequer nearly thirty years later, in 1651.

The records of the Equity Court of Exchequer – held at The National Archives – are a rich source of information for those interested in local history, as disputes were arranged by county and often concerned local matters, such as non-payment of tithes or customs of a particular town. The case of John James’ wine licence is just one of thousands of Hampshire cases recorded in these collections between 1558 and 1841 (the duration of the Court of Exchequer’s equity side).

To tell the full story of this dispute, several record series need to be consulted, as records created by courts such as Chancery and Exchequer are separated into different series according to their document type. Pleadings start the case, with the plaintiff’s bill of complaint and the defendant’s plea, or answer, to this complaint. For the Court of Exchequer, these pleadings have the modern document reference E 112. After the pleadings came the proofs, the statements made by the defendants and witnesses in the case (as well as any documentation to prove/disprove the complainant’s claim). These statements, known as depositions, are collected in E 133 and E 134, depending on where these statements were taken. If the depositions were heard before the Barons of the Exchequer in Westminster or London, then they are collected in E 133. If, however, special commissions were sent out to the counties for depositions to be taken there, then the records are held in E 134. Finally, the court would make its judgment. For Exchequer, these are recorded in decree and order books in E 123-127.

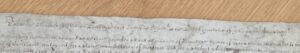

The Pleadings (E 112/334, item 9)

John James Bill. Description: John James’ Bill of Complaint

John James’ initial grievance is described in his bill of complaint, collected with other pleadings for this case in E 112/334, item 9. To find individual cases like this one, researchers need to consult manuscript finding aids held in the Map and Large Document Reading Room at The National Archives in Kew. These finding aids, like the series itself, are arranged by reign then by county. For this case, which commenced in 1651, the Hampshire entries – described in the early modern period as Southamptonshire or County of Southampton – were consulted.

E 112 Indexes Map Room. Description: Index books for Exchequer Bills & Answers, held at The National Archives, Kew

James complained that he was owed rent by those who had leased the Bugle from him. In 1636, he and his sisters had leased the Bugle and the associated wine licence to Robert Goter of Newport, innholder. Goter’s answer to the bill of complaint confirms this, and that he paid James £14 a year for the inn and wine licence. However, the effects of the civil wars on Goter’s estate left him unable to pay this rent from the mid-1640s. Therefore, Goter borrowed £200 from Giles Barnes, an innkeeper in Southampton, and as surety for this loan set over his interest in the inn, plus any profits from the retailing of wine there, to Barnes.

Giles Barnes confirmed this series of events in his answer to James’ bill, adding that Goter had three years to pay back the £200. During this period – between September 1646 and June 1649 – Goter was allowed to remain in the inn called the Bugle (where he was living) and continue to use the profits of the said inn and attached wine licence to work off his debt. However, when the time came for the £200 to be repaid, Goter was unable to pay back the debt. Nevertheless, Goter gave him a further year to pay back the money.

By May 1649, Giles Barnes himself owed £700 to William Bulkley, a merchant living and working in London. As Goter had failed to repay Barnes, the lease of the Bugle and the wine licence was transferred again, this time to Bulkley, until Barnes could repay him. As Bulkley was living in London, in August 1650 he asked his father-in-law, Peter Clungeon, also a merchant, to visit the inn and manage his interest in it. Clungeon’s answer to the bill of complaint confirms these negotiations. When he arrived at the Bugle, he found Goter still living there, as per the agreement between him and Barnes. As Clungeon and Bulkley did not wish to throw out Goter and his servant, James Norman (who was a vintner), they came to an agreement with Goter and Norman that they could remain at the inn as long as they paid a portion of their profits from retailing wines there to Clungeon and Bulkley.

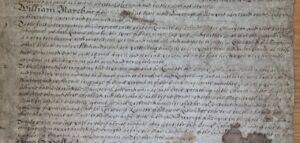

Bulkley Answer. Description: “The several answers of William Bulkley, merchant, one of the defendants to the bill of complaint of John James, complainant”

All the while, James was receiving the rents from Goter. His bill of complaint, made late in 1651, complains that these payments had fallen short, and he named all these men – Robert Goter, Giles Barnes, William Bulkley, and Peter Clungeon – as defendants in this Exchequer action, to try and receive what he thought he was owed. The documents in E 112/334, item 9 contain James’ bill and the answers of Goter, Barnes, Bulkley, and Clungeon. But, these pleadings only tell part of the story. To find out what happened next, we need to consult the depositions.

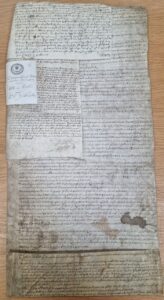

The Depositions (E 134/1655/Mich9; E 134/1656/East5)

Depositions. Description: Interrogatories and Depositions relating to the case

Exchequer cases could take several months, if not years. As such, it wasn’t until July 1655 that commissioners were appointed to question witnesses on the behalf of John James. By this point, Robert Goter – who had originally rented the inn from James – had died, but that didn’t mean James’ grievance was resolved. He still felt that he was owed money by the surviving defendants.

John James Interrogatories. Description: Interrogatories to be put to witnesses on behalf of John James

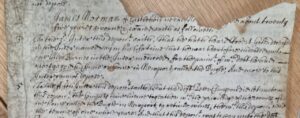

Many of the questions put to the plaintiffs’ witnesses concerned the original lease of the Bugle and the various assignments that had occurred since then. The interrogatories, the questions put to these witnesses, include a question asking when Robert Goter died and who was responsible for the rent of the inn at the time of his death. James Norman of Castlehold near Newport, 25 years old, gave the most detail regarding this. He had been a servant of Goter and was involved in the lease from Peter Clungeon and William Bulkley (as described in the pleadings). He confirmed that following Goter’s death, a man named William Thomas retailed wines in the Bugle until late in 1655, after which William Doe, innholder, took over the wine licence. Norman also confirmed that Goter’s lease had passed to his heirs Thomas and John Goter.

James Norman Deposition. Description: The deposition of James Norman, confirming that Robert Goter owed Giles Barnes money

However, though James’ original complaint concerned the lease of the Bugle and its associated wine licence, by the time these interrogatories were drawn up in 1655 James had a new grievance with the defendants, and with the mayor and bailiffs of Southampton. Many of James’ interrogatories put to deponents such as John Delamotte, former mayor of Southampton, concern the events of 19 February 1652. The Exchequer case was already ongoing by that point, but on this day John James appeared before Delamotte, then mayor, with a bloodied face. James claimed that William Bulkley had attacked him. Yet, according to the interrogatories and depositions, it was James that ended up imprisoned in the Bargate at Southampton, for breaching the peace. His accuser for breaching the peace, the other defendant Peter Clungeon. Each of the deponents that answered this question agreed that James appeared before them bloodied but did not know who had caused these injuries.

In his interrogatories, John James accused the former mayor and his constables of refusing him bail and keeping him imprisoned even though he was a burgess of the town. Each of the deponents refuted this claim, saying bail was not offered to James and he was only imprisoned until his case could be heard at the town’s quarter sessions. The former mayor and constables did concede that these quarter sessions – which customarily would have been held four times a year – were only held once a year as the recorders for Southampton lived a long way away. As such, James was in gaol for seven months in total.

Delamotte Deposition. Description: Deposition of former mayor John Delamotte, confirming that James had appeared before him bloodied and that the quarter sessions were now only held once a year

These depositions reveal a whole other side to the case, and shine a light on the administration of local justice in seventeenth-century Southampton. These records, too, provide a lot of information about the deponents providing these statements. Their ages and occupations are often specified, and, in this case, we hear from a number of men involved in the running of Southampton in the 1650s.

But, in terms of progressing the Exchequer case, these depositions say little, other than confirming the statements provided in the pleadings concerning who was liable to pay rent on the Bugle and its wine licence.

Deft Depositions. Description: Depositions collected on the behalf of the defendants William Bulkley and Peter Clungeon

Another set of interrogatories and depositions, this time on the behalf of Bulkley and Clungeon, further add to the detail of this case. The commission for these depositions was made on 12 February 1656. From James’ interrogatories and the responses to them, we got the impression that James may not have been as upstanding as his pleadings claimed which, considering those statements were made by and on behalf of James, was no mean feat. You would expect those documents to paint James in a wholly favourable light. The interrogatories and depositions made on behalf of the defendants, on the other hand, pull no punches at discrediting James. The first interrogatory explicitly asks whether John James was “a very troublesome and contentious person, much addicted and given to suits in law against his neighbours”. Worse still (for James at least), every deponent that answered this question said that he was particularly litigious against his neighbours. The second interrogatory wasn’t much better, asking whether James was a “very abusive and disorderly person” much given “to drunkenness, quarrelling, and fighting”, who when drunk was known to break people’s windows and generally cause disruption, who when brought before the magistrates would pretend to be mad to avoid punishment. Again, all the deponents, men who lived and traded in Newport and knew John James and the defendants well, confirmed that this was typical of James. William March, one of the sergeants at mace in Newport, said that he had served as an officer in the borough for 22 years, and so could confirm first-hand that James would regularly claim madness to avoid punishment. Edward Hall, a haberdasher based in Newport, confirmed that when James was drunk he was “addicted to break people’s glass windows, to catch or snatch people’s wares from the stalls of their shops, and tread and trample the same in the street under his feet”.

William March Deposition. Description: Deposition of William March

These depositions also confirmed the various leases made of the Bugle and its wine licence, but added that they did not believe that James was not receiving rent. Again, James Norman’s deposition proves crucial. He did not believe that Robert Goter owed John James any further rent, because if he did James would have claimed it on one of his many visits to the inn. According to Norman, James would often frequent the inn for weeks at a time, making himself sick with drink, and he would eat, drink, and lodge free of charge. During these visits, Norman claimed that Goter also paid James rent.

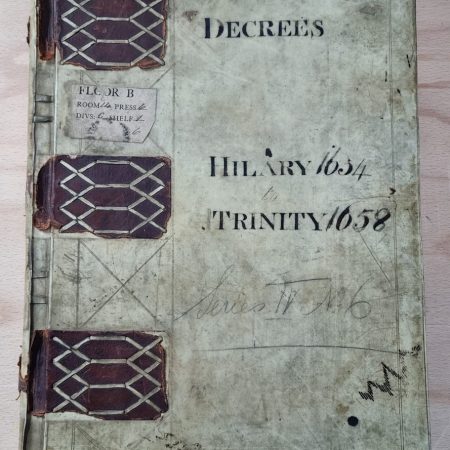

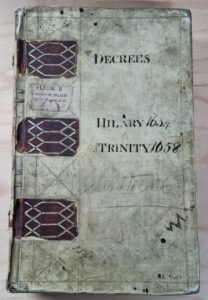

Verdict (E 126/6)

Decree Book for Exchequer. Description: Decree Book for the Court of Exchequer, giving the verdict in the case

Finally, in November 1656, the Barons of the Exchequer gave their verdict in the case. But even then it wasn’t simple. Initially, on 10 November 1656, the judges agreed with the argument that the defendants made that the matter should be heard at common law, because it amounted to a debt dispute between private parties. But, they were willing to keep the case in the Exchequer if John James could produce the original letter patent to prove that it was a matter for the court. However, when prompted to produce this paperwork, James was unable to, and so James was ordered to produce the grant at his earliest convenience, and to pay the defendants 40 shillings for their costs for this delay.

A week later, on 17 November, John James declared that he had the relevant paperwork. This time it was the defendants who were unable to appear. Therefore, James’ original fine of 40 shillings was voided and the case was adjourned until the following Monday, being 24 November 1656, when the barons issued their verdict. The judges were little interested in the assault claims and disreputable behaviour of the complainant, and instead judged the case on the original grievance, the yearly rent of £14 reserved upon a lease of a wine licence in Newport and for the arrears of the said rent. Unfortunately for John James, the letter patent he brought in did not prove that the said wine licence was assigned to any of the said defendants, and therefore did not prove that the defendants ought to pay him any rent. The judges found against John and ordered him to pay the defendants £3 for costs.

Final Verdict. Description: The final verdict, finding in favour of the defendants

The Court of Exchequer, based in Westminster and initially only concerning matters of Crown finance, may not be the most obvious place to research local history. However, this case of the seventeenth-century Newport wine licence shows that the records of the Court of Exchequer are full of information of interest to the local historian. But this is just one case. There are hundreds, if not thousands, more Hampshire stories waiting to be told from these collections. It takes a little digging, but the information these records contain is often worth it.

Further Reading

W. H. Bryson, The Equity Side of the Exchequer (Cambridge University Press, 1975)

The National Archives’ Research Guide to the Court of Exchequer (https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/court-exchequer/)

Author: Dr Dan Gosling

Bio: Dr Dan Gosling is Principal Legal Records Specialist at The National Archives, expert in the records created by the central law courts and the litigants bringing cases into these courts. His PhD (University of Leeds, 2016) examined statute interpretation in the late medieval and early modern periods. He is co-author of the recently released book A History of Treason The Bloody History of Britain through the Stories of its Most Notorious Traitors (2022).

Follow Dr Dan Gosling on his Twitter profile @TheGozfather