‘Anglo-Saxon charters’ refer to a wide range of documentary sources including diplomas, writs and wills, written in a combination of Latin and Old English. Typically, these refer to land grants by the king to one of his subjects, either a member of the church or a layman. Diplomas often granted a subject land, while writs were written instructions, which may have contained a royal command or the settlement of a dispute. These charters would have been witnessed by the king and his most powerful secular and ecclesiastical vassals, from archbishops to abbots and ealdormen to thegns. Anglo-Saxon kings did not have a settled court, rather they travelled their kingdom hosting royal assemblies, where these powerful figures would meet for an extended period of feasting and celebration, or to fight for a chance for an audience with the king. For the king, they were an opportunity for him to bring his vassals together and make a show of his own strength, and perhaps keep an eye on potentially unruly ealdormen, a precedent set by Æthelstan (r.924-927) whose assemblies were larger than any of his predecessors. This practice was a requirement of Anglo-Saxon kingship. Unlike their neighbours on the continent, English monarchs of this period required the consent of their most senior magnates to pass any decree. Thus, rather than being able to remain in one location issuing orders as they pleased, Anglo-Saxon kings were forced to hold assemblies across their kingdoms, where a flurry of charters could be produced in a short amount of time.

BL Royal MS 14 B VI, f.3r (2022) <https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=royal_ms_14_b_vi_f001r> [accessed 25/08/2022]

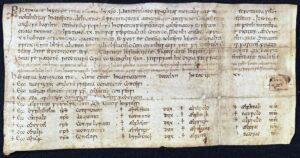

The result of this is the presence of witness lists at the end of charters. These are the signatures of consent of the most powerful men and women in the realm, agreeing to the king’s decree and backing up his royal command. The order of names in witness lists can be seen as a sign of the influence particular individuals had at any one time. The king and sometimes direct members of his family would often come first in the witness list, followed by the most powerful religious figure in the Kingdom (by the tenth century, this is almost always the Archbishop of Canterbury), followed by the realm’s most influential ealdormen, the equivalent of lords and dukes in later medieval society. Even the handwriting in a particular charter can tell us a lot about the extent of a king’s influence at any one time. There has long been a debate about the centralisation of charter production, whether Anglo-Saxon kings might have had their own royal chancery or relied on local rulers to provide this service as they travelled. Consistency in the handwriting in a king’s charters suggests the same scribe reappearing time and time again, while frequent changes to the script featured in a charter might suggest that the king was using the administrative services of a local church or magnate. This is made clear by the change in the style of charters produced north and south of the Thames following the division of England between the brothers Eadwig and Edgar in 957. Eadwig, who ruled south of the Thames and kept control of London, Winchester and Canterbury saw his charters formulated in the same manner as they had been produced since the 920s, whereas Edgar, who ruled north of the Thames and would have drawn on scribes educated under different traditions, produces stylistically different charters written by a visibly different hand, but in the same square miniscule script. This is why charter analysis is so important to the study of Anglo-Saxon kingship, and particularly England as it was governed during the tenth century, when political instability ran rampant while our modern understanding of England came into being.

The tenth century is widely regarded as the period in which the Kingdom of England became a political reality. Following the death of Alfred the Great in 899, a period of conflict, expansion and consolidation saw the Kingdom of Wessex, with its core in modern day Hampshire and Dorset, push its authority northwards until it oversaw more or less what today are England’s modern boundaries. This expansion was neither easy, nor linear, though. Wessex had been left as the dominant Anglo-Saxon kingdom following the devastation wrought by the Great Heathen Army and subsequent Scandinavian settlement of the ninth century, with the old Kingdoms of Northumbria and East Anglia essentially destroyed, and Mercia left as a rump state half under the control of Wessex and half under the control of a plethora of Scandinavian rulers in concert with local Anglo-Saxon authorities, people who held strongly to regional identities and often saw the West Saxons as outsiders. Because of this, the Kingdom of Wessex had to fight constantly to maintain its authority over the region. Alfred’s children, Edward (r.899-924) and Æthelflæd (r.911-918), who ruled over Wessex and Mercia respectively, would conduct joint military campaigns to conquer those regions of the midlands which had fallen under Scandinavian control, as well as what had once been the Kingdom of East Anglia. Æthelflæd’s death in 918 left a power vacuum which Edward quickly seized upon. He had already stationed troops in Mercia, and was under the process of occupying existing fortifications, building new ones, and improving the bridges and roads which linked his own kingdom with his sister’s.

Later in his life Edward would spend time campaigning in Nottingham, Manchester and the Peak District as well as Northumbria, where he is said to have met with Scottish Kings. He was succeeded by his son Æthelstan, the first individual to refer to himself as ‘King of the English’ in written sources, and the first monarch to control all of what we now call England, after his annexation of York in 929. England’s consolidation was far from over though, as conflict with both Scandinavian settlers and other Anglo-Saxon Groups in Mercia and Northumbria meant that portions of the kingdom frequently broke off and had to be reconquered. York left the kingdom after the deaths of Æthelstan and Edmund in 939 and 946 respectively. Edmund (r. 939-946) and his successor, Eadred (r. 946-955) would both have to fight to reconquer the territory and Eadred would face significant resistance and rebellion throughout his reign. Upon Eadred’s death in 955, he was succeeded by his fifteen-year-old nephew, Eadwig, who inherited a fragmented Kingdom with strong regional identities and powerful local magnates seeking to assert their authority over their new boy king.

Eadwig’s predecessor was his uncle, Eadred, who appears to either have suffered from a prolonged period of illness or been on military campaign in Northumbria for much of his reign, delegating many of his kingly duties to other members of his court. Perhaps the two most powerful men during the reign of King Eadred were Oda, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Dunstan, the Abbot of Glastonbury and a close friend and advisor to the three sons of Edward the Elder who had served as king: Æthelstan, Edmund and Eadred. A new style of charter, labelled as the ‘Dunstan B’ charters, appears in 951. These charters are set apart by their unique use of an invocation and proem at the beginning of the charter. An invocation calls on God to bless the authority of the king in settling this particular matter, while the proem acted as a preamble to justify the production of the charter, often reflecting on the shortness of human life and the importance of leaving written record of settlements. These charters flourish between 951 and 955, in the final four years of Eadred’s reign, before disappearing at the beginning of the reign of Eadwig in late 955. This represents a massive shift in authority as Eadwig brought back the responsibility for charter production solely back into the hands of the king, and stripped Dunstan and Oda of a huge source of power that they may well have intended to keep after Eadred died and a fifteen-year-old took the throne. Eadwig’s deteriorating relationship with Dunstan would culminate with a furious confrontation following his coronation. The Vita Dunstani, a hagiography of Dunstan, claims that this was the result of Eadwig dishonouring his position as king, shirking his duties and ignoring Dunstan’s advice, while later historians have argued that it is equally likely that Eadwig, who had already stripped Dunstan of his authority to produce charters, did not react well to the Abbot’s overbearing presence at court as he attempted to maintain his grasp upon the influence he had held under Eadred. Sometime after Eadwig’s coronation in 956, Dunstan fled England in exile in Flanders after what could only have been an agonizing fall from grace. Following his ascension and seizure of power, Eadwig would embark on a rapid policy of land distribution in England, seeking to bolster loyal men and counter the influence of former powerful figures.

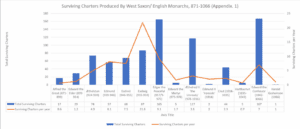

87 charters survive from Eadwig’s reign, an unprecedented number for someone who only ruled for four years (955-959). For comparison, there are only three Anglo-Saxon kings for whom we have more surviving charters than Eadwig: Edgar, who ruled for sixteen years (959-975), has 165 charters surviving him. Æthelred the Unready, who ruled for thirty-eight years (978-1016) has 117 charters surviving him, and Edward the Confessor, who ruled for twenty-four years (1042-1066) has 167 charters surviving him. By analysing the contents of these charters, what can be seen from Eadwig’s reign is a policy of the rapid reassignment and granting of land in Hampshire. 57 of Eadwig’s 87 charters reference the granting of land to a layman, many of whom are new nobility, suggesting the promotion of lower status men to build a loyal powerbase, mostly in Wessex, or the modern-day counties of Hampshire, Dorset, Berkshire, Wiltshire and Somerset. By studying the witness lists included in these charters, the growing influence of Eadwig’s new nobility and the decline of the old guard can be clearly seen. Prior to the English reformation and dissolution of the monasteries in 1536, the majority of Eadwig’s charters were held at Abingdon and Winchester, 30 at Abingdon and 22 at Winchester. Today, these charters are distributed across the country. The British library holds over 200 charters, 5 of which were produced during Eadwig’s reign. One is held at Hampshire Archives and Local Studies in Winchester. The remainder are held across the country in both public and private collections.

While Oda of Canterbury kept top spot amongst Eadwig’s religious influences, he appears to have promoted Ælfsige, bishop of Winchester, who would have held vast lands across modern day Hampshire at this time, to second place in these lists. Brithelm, bishop of Wells is promoted from around seventh, to fourth and then second in the witness lists. This rise in influence is further proven by the fact that Eadwig chose him to succeed Oda as Archbishop of Canterbury in 959, at which point he takes the top spot amongst religious witnesses. Eadwig’s policy resulted in backlash in 957, though. In this year, the kingdom was divided along the Thames. Eadwig would rule directly in the south while only nominally in the north, where his brother Edgar appears in charters listed as ‘King of the Mercians’ (the Midlands today) while still paying some homage to Eadwig.

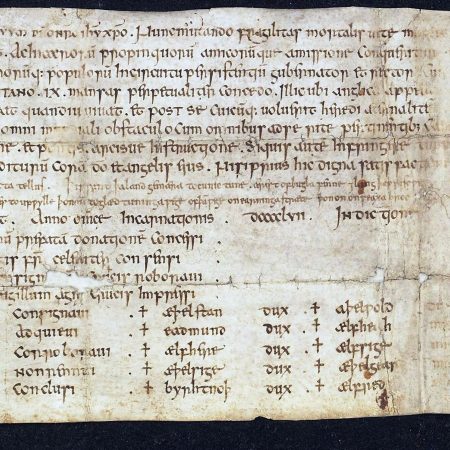

This charter, S649, records the granting of land at Connington, Huntington to his ‘minister’ Wulfstan. The signatures of Eadwig, his brother Edgar and Oda, Archbishop of Canterbury can all be seen alongside

Courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Winchester Cathedral: Hampshire Record Office, DC/A1/5

Æthelstan half-king was an extremely powerful nobleman who controlled lands in East Anglia and parts of the Eastern Midlands, who had come to power in the 930s. He was an ally of Oda and Dunstan and sits at the top of Eadwig’s witness lists until 957, at which point he disappears from the witness lists following the division of the kingdom. In Eadwig’s charters he is replaced by Edmund, who was based in Wessex, who had been granted land by Eadwig previously and had made his way up from roughly fourth to second in previous witness lists. North of the Thames, in Mercia, the power vacuum left by Æthelstan half-king is filled by Ælfhere, another earlier beneficiary of Eadwig’s land grants who had made his way up from as low as seventh to third, and on several occasions first, on Eadwig’s charters before the division. Ælfhere and his brother Ælfheah would be given large grants of land in the south and midlands, with Ælfheah being the beneficiary of three charters in Eadwig’s reign, granting lands in Ellendun, Wiltshire (S585), Buckland, Berkshire (S639), and Nadder, Wiltshire (S586). Eadwig granted little land in modern day Hampshire to his nobles, likely because the vast majority of land in this territory was owned either by the Bishop of Winchester or by the king directly, who did not want to give up his own estates so close to Winchester, which was the seat of the royal family’s power at this time and a common location for the assembly of England’s most powerful nobles. Instead, he appears to have granted land surrounding these regions to lesser nobles, to build a strong, loyal powerbase in the south who owed their fortunes to him directly.

Eadwig would die somewhat suddenly in 959 at the age of nineteen, possibly from illness, although exactly how is unclear. While he was successful in removing obstacles to his power at first, the speed at which he promoted new nobility and froze out powerful figures like Dunstan led to the division of the kingdom in 957, causing the decline of his authority north of the Thames. While there is no existing treaty which exists to record the terms of this division, charter analysis is key in showing us that even though Eadwig’s authority took a hit, he still ruled all of England at least nominally, while a political titan in Æthelstan half-king was removed in favour a more loyal figure to Eadwig. Primary sources from tenth-century England are unfortunately extremely lacking, and for centuries narrative histories and biographies commissioned by the church remained our best source of information from this period, sources which are clearly going to contain a heavy weight of bias. Charters, while not perfect, offer an excellent insight into the nature of court politics and the relationship between kings and vassals at this time, and can be analysed in concert with other sources available to construct a more well-rounded, objective understanding of such a turbulent and fascinating period.

Books Referenced in this Blog Post:

Keynes, Simon, The ‘Dunstan B’ Charters. Anglo-Saxon England, pp.165-93 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, vol. 23, 1994).

Maddicott, J. R. The Origins of the English Parliament, 924-1327 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2010).

Molyneaux, George. The Formation of the English Kingdom in the Tenth Century (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2015).

Roach, Levi, Kingship and Consent in Anglo-Saxon England, 871-978 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2013)

Whitelock, Dorothy, transl., English Historical Documents, i: c.500-1042, Second Edition (Eyre Methuen, London, 1979).

Online Resources:

ESawyer: https://esawyer.lib.cam.ac.uk/about/index.html

Author: Josh Hayden

Bio: Josh completed his Masters Degree in Medieval and Early Modern Studies at the University of Kent in 2022 and his dissertation focused on the relationship between the monarchy, church and nobility in the nascent Kingdom of England during the middle of the tenth century. His interests lie in the development of political institutions within England and the preceding Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms. Josh is currently studying towards a qualification in Archives and Records management at the University of Dundee while working at Hampshire Archives and Local Studies