As a researcher of medieval history, one of my favourite parts of archival work is the actual handling of documents, some of them centuries old. In museums the handling of artefacts of a similar age is typically protected against with hermetically sealed glass cases and the like, however, when visiting an archive, you can be up close and personal with a piece of history which has survived longer than any museum which is open today. In this vein archives are not only valuable for the records they hold but for the tactile history that can be interacted with. Medieval wax seals, which I have previously written about for HAT, are perhaps the best example of tangibly connecting with history due to intricate detail engraved by artisans on the original seal matrix (stamp which made the impression) sometimes even preserving finger or palm prints left by the seal’s owner. With the popularity of interactive exhibits in museums, interactive experiences of historic material from archives in various forms similarly strengthens the public’s connection with cultural heritage. I was fortunate enough last year to work on such a project bringing medieval seals, the very making of them, into the hands of the public.

Last year I was approached by Hyde900, a community project in Winchester who research, archaeologically excavate, and hold community events celebrating the history of Hyde in Winchester, about reconstructing a medieval seal matrix of Hyde Abbey for their Festival of Archaeology and Heritage Open Day events. As I used to volunteer at the Winchester College archive, I was familiar with the wealth of surviving great-quality medieval seals held there and had been increasingly curious about using 3D technology with history, mostly 3D printing, though this project involved the use of 3D scanning. The project would involve scanning one side of the abbey’s seal, then later digitally inverting the 3D model to reconstruct the matrix which would be 3D printed and used on the community days alongside a traditionally engraved obverse by Chris Prior.

Hyde Abbey, a former Benedictine monastery, used to stand just outside the North Walls of Winchester before the dissolution of the monasteries by King Henry VIII. The abbey’s first ‘form’ was founded in 901 when King Edward the Elder built a minster, commonly referred to as the ‘New Minster’, not far from where the current cathedral stands today. However, the minster building which has been marked out next to the current cathedral is that of the ‘Old Minster’, a church first built in the mid seventh century, the New Minster stood closely to the North of this building. After the Norman conquest in 1066 the new cathedral, which began construction in 1079, was to be the central point of ecclesiastical life in the city and later in 1109 Henry I ordered the New Minster community be removed to the suburb of Hyde, where the new monastery – Hyde Abbey was built. Notably buried in New Minster, then later moved to Hyde Abbey, were the kings Alfred, Edward the Elder, and Eadwig. Much plundering and dismantling befell the abbey after it was dissolved in the 1500s which led to remains of these kings to be destructively dispersed. Following the exhumation of an ‘unmarked grave’ on the site, where a Victorian vicar had haphazardly reburied various bones he had found, archaeologists and osteologist Dr Katie Tucker from the University of Winchester found that one fragment of a pelvis bone belonged to an older adult man from 895 to 1017, suggested it likely belonged to either King Alfred or King Edward the Elder.

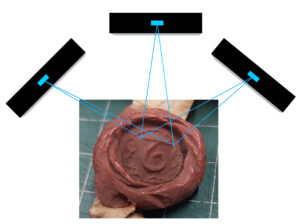

Returning to the 3D scanning – I had become much more interested in the utilisation of 3D technology and history through an article I had been co-authoring with Professor Ryan Lavelle of the University of Winchester. The article discussed a methodology for using 3D printing and the archaeological research to produce tangible models for both learning and academic use, specifically focusing on the Old Minster in Winchester as a case study. The process for 3D scanning, however, was quite different. Much like how a smartphone stitches together singular photos when creating a panoramic photograph, 3D scanning takes high-detail distance measurements of and between features of an object from reflected laser light emitted by a scanner. When the scanner is moved around the object new measurements are taken and then stitched together to calculate how features of the object are three-dimensionally related to each other. This is better understood via the drawing below where the scanner is positioned in three separate positions taking independent measurements from the laser light to certain features of the seal. The diagram below focuses on just two features, the two ends of the top of a capital ‘T’, whereas in practice the scanner is taking measurements for everything the light’s view.

Diagram depicting how a 3D scanner would scan an object. Specifically using a seal attached to document: Winchester College Archive, 14672.

Although there are a number of surviving documents in the archive of Winchester College with the corresponding seal of Hyde Abbey, the best surviving example was chosen to be scanned to produce the clearest 3D model. The particular document which the chosen seal was attached to was a lease made in 1537 between John Selcot, the Bishop of Bangor and at the time the Commendatory of Hyde Abbey (essentially the controller of the abbey’s revenues), and Richard and Joan Erle, of the manor of Abbots Worthy (about 2 miles North East of the abbey) for 41 years. The abbey had accrued a considerable amount of local land by this point and had done so since the monastery’s original building in the tenth century. One of the Hyde900 group’s best qualities is that it gives back to the local community through the researched heritage of the area, so to be able to contribute the added local value and interest of the small village of Abbots Worthy was a nice extra addition.

Scanning the Hyde Abbey seal using a Revopoint Mini 3D Scanner.

Below is the specific side of the seal I was tasked with next to the result of the scanning. On this side of the seal are pictured the three patron saints of the monastery (from left to right): St Grimbald, St Barnabas, and St Valentine who is holding his severed head, despite having one attached at the neck. This also includes ‘caption-like’ notes of which saint is which and is totally surrounded by the Latin text of HYDA – PATRONORUM – JUGI – PRECE – TUTA – SIC – HORUM, which translates to ‘May Hyde be protected by the constant prayers of its patrons’. Grimbald had been the first abbot of the New Minster and died very soon after it was built in 901, whereas Barnabas and Valentine became closely associated with the monastery due to the abbey having supposed relics of the two saints. Queen Emma, wife of Aethelred ‘the unready’ and Cnut, donated a relic of the head of Saint Valentine to the monastery in 1042.

Left: One side of the Hyde Seal from 1537. Right: The digital scan of the same side of the seal.

After obtaining the scan of the seal (above) I digitally cut out the attached parchment tag which connected the document and the seal before inverting the model, turning the raised wax impression into a cavity form of the original seal, and placing it in a ‘typical’ design of a seal matrix of this size (see below). These larger seal matrices would have the additional lugs at the side to perfectly align both matrices so to include this aspect in the final design would ensure that participants would be able to come away with an alike perfectly aligned seal.

The digital 3D model of the final reconstructed seal matrix.

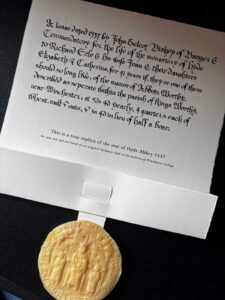

The result of the final design, when used in tandem with Chris Prior’s complimentary matrix, allowed for Hyde900 to continue to offer this interactive experience beyond the Festival of Archaeology event in 2024 and have recently enjoyed great community involvement during the September 2025 Heritage Open Days event. During the most recent event, the public were invited to learn how to use a specifically made wax (made mostly of beeswax) with the matrices to produce a faithful seal impression which itself was attached to a piece of parchment describing the original lease document.

The final reconstructed and impressed seal with the offered charter by the Hyde900 group.

The outcome of this process was a great success through bringing the rich heritage of Hyde to the community through an active and tangible interaction with history. The process and learning required to 3D scan, digitally manipulate the model and then reconstruct the matrix was very complex and time consuming, however, the benefits of being able to bring such an activity which bridges the gap between public engagement and historical handling is a great example of why more should be done. In addition to using 3D scanning for reconstruction its uses have been pushed increasingly further in recent years and includes companies such as Cotswold Archaeology allowing the public to view 3D models of artefacts, previously untouchable to the non-archaeologically minded, online for free. Although this project used a commercial 3D scanner, as is common with artefact scanning, the rate of growth which 3D technology has been seeing recently has led to anyone being able to scan any item of interest using their own smartphone. In this regard cultural heritage has and will continue to lend itself perfectly to this field as it means that heritage can not only be preserved digitally but also can be shared, viewed, and enjoyed by anyone anywhere.

Author: Jacob Newbury

Bio: Jacob is currently a PhD research student of History at the University of Winchester, where he is studying the Newburgh family, a gentry family in Dorset during the Fifteenth Century. His passion for the high and late Middle Ages, particularly the origins of heraldry and social history, was sparked by six years of independent research into his own family’s history. As an undergraduate, he was the lead co-author on a published paper with Professor Ryan Lavelle on using 3D printing to reconstruct archaeological findings for academic and pedagogical purposes. He also works as a freelance family history and archival researcher.