Physician Dr John Latham (1740-1837) retired to Romsey in 1795 to be near his son, a brewer with a chain of inns. For 20 years he immersed himself in the history of the town and its abbey, with a view to publication. He lived in a substantial house in Middlebridge Street, now replaced by Stephens Court.

Unfortunately, events overtook him. His son engaged in an ambitious plan of expansion, relying on his father and others to put up the money. In 1817 it all came to an end, when it was discovered that he had committed fraud and was declared bankrupt. The full story has been told by local historian Barbara Burbridge (The Latham Bankruptcy, 1817. Pots and Papers, Journal of the Lower Test valley archaeological study group, 6, Autumn 1994: 21–32).

For the elderly physician, already in his late seventies, it was a disaster. He had to sell his house in Romsey and move to Winchester to live with his daughter, Ann, and her husband, the surgeon William Nicholas Wickham. And it got worse: his son committed suicide.

He took with him seven volumes of his precious notes on Romsey, but they never got to print. They eventually ended up in the British Museum (now the British Library), where they were scarcely ever consulted. Fifty years ago, local historian Phoebe Merrick found references to them whilst studying at King Alfred’s College, Winchester, and decided to give them a look.

On a day trip to London, she had no trouble finding the notes in the catalogue, but when the librarian came to retrieve them they were in a locked cabinet without a key! It took several hours to find a locksmith, before Phoebe could for the first time lay hands on the papers. And she was not disappointed.

She said: ‘I was immediately charmed by the pictures and fascinated by the huge amount of information there was on Romsey. It was all completely new to me, as at the time I had done virtually no local history. But I recognised their value and kept alive the idea that one day they should be published.’

Forty-five years ago the LTVAS – to which the Romsey Local History Society belongs – purchased a microfilm of all seven volumes and the late Pat Genge typed up the entire contents, with the exception of the references and long passages in Latin, mainly from the registers of the Bishops of Winchester. These were later transcribed by Barbara Burbridge from the originals held by the Hampshire Record Office.

Phoebe then edited all the material and prepared it for publication. A major task was tracing all the sources that Latham had used. He made careful records, but used abbreviations that required help from the University of Southampton’s Hartley Library, especially Professor Chris Woolgar.

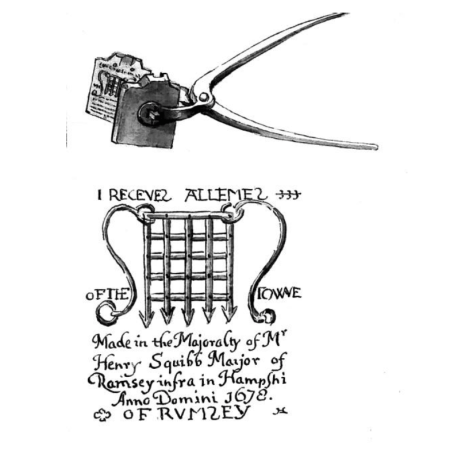

Now available as a set of four volumes, Latham’s notes, with thousands of footnotes, are a unique source of information on Romsey – and other places – collected in the early years of the nineteenth century. He was meticulous and recorded everything he saw. He also made sketches and collected others. Many items have now disappeared or been defaced. Latham also faithfully recorded the pews in the abbey and their occupants in his day, providing a snapshot of the ‘great and good’ of the town.

He recorded many memorials now lost and collected stories, like that of the eccentric Joseph Fyfield, lord of the manor of Stanbridge Earls, who was so parsimonious that he refused any repairs to his house. Latham records that he lived “with the roof…open to the heavens…with the joists and floors rotting”. All this and much, much more is included in the second volume, which deals with “people and places”. Another volume covers the administration of the town.

The whole work is indexed in fine detail, with an extensive bibliography. It is essential reading for anyone with an interest in local history, not only of Romsey, but of Hampshire as a whole.