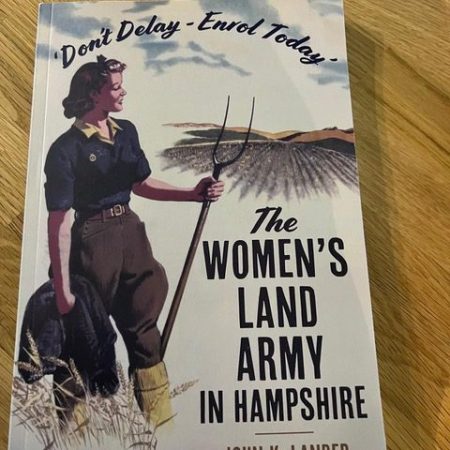

Re – Don’t Delay – Enrol Today; The Women’s Land Army in Hampshire, written by Dr John Lander, published by The History Press, (£15.99, plus £2.10 for postage) from the author at jandplander@btinternet.com

Our three children, once they reached adulthood, have never been backward in coming forward with perceptive comments. One of them said recently; “Dad, most writers have given up by the age you started!” – a true enough observation. It was not until our youngest went to university in 1989, that I said to myself, “It’s my turn now” and, as a very mature student, enrolled with The Open University. That was a life-changing decision, leading to an Honours degree in 1995 and a PhD in 2000. A reviewer of one book accurately and succinctly described me as ‘a banker by profession and a social historian by natural inclination.’

A fascination with 19th-century history of British nonconformist churches and the teetotal movement has, since publication of Itinerant Temples, a book based on my PhD thesis, prompted the writing of five more, as well as around twenty-five papers for specialist journals. My last project was the history of Sparsholt College, A Place of Transformation, published in 2022. Like the experience of many historians, research uncovered several other potential subjects for study. Two have since been fulfilled; the first was the discovery that seven former Sparsholt students were killed in action in the 2nd World War but there was no memorial to them anywhere on the campus. I was able to trace descendants of six, gained their ready cooperation and, accompanied by a booklet giving biographical details, there is now a commemorative bench, with all seven names engraved on it, situated around the War Memorial in Sparsholt’s village centre.

The other realisation was that the normal pattern of Sparsholt’s instruction focussing on preparing students for land-based jobs was abandoned for much of both world wars with resources devoted to training women and girls for work on Britain’s farms. It quickly became apparent that enough primary and secondary material was available to produce a full picture of the role of the Women’s Land Army in Hampshire. Documents at the Hampshire Record Office include papers relating to a government National Service Committee as it affected Winchester City Council, minutes of Sparsholt Farm School Special Sub-Committee meetings, a draft tenancy agreement for a hostel and, for the 2nd World War, minutes of what was then the County Farm Institute, Sparsholt, two volumes of Student Registers, and a copious amount of correspondence. Sparsholt College’s librarian has been a great help in identifying relevant material held there, including many pictures. And, of increasing value to historians, is the British Newspaper Archive. For much of the first half of the 20th century no fewer than seven local papers provided Hampshire news.

Access to written material is imperative, but the opportunity to meet with two women, both born in the 1920s, who served in Hampshire’s Women’s Land Army, as well as descendants of other land girls, has been a special privilege. Their personal reflections, and access to memorabilia that families have retained, have added a valuable dimension to the overall story.

Don’t Delay – Enrol Today was an advertising slogan to encourage women and girls to apply to join the Women’s Land Army. The organisation was first established by the government in early 1917, by which time the First World War was already in its third year, and re-formed, anticipating the outbreak of the Second World War in June 1939. The recruitment, training and placement of “land girls” as they became universally known in the Second World War resulted from the fact that hundreds of thousands of men working in agricultural enterprises were required to join the armed forces. Furthermore, increased home food production was essential as 60% of Britain’s food came from abroad, and German U-boat activity was seriously disrupting the arrival of imported goods.

Hampshire was, arguably, the first English county to begin the instruction of land girls at the Farm Institute, Sparsholt, and elsewhere, and pro-rata to its population, placed more of them in agricultural settings than any other. The range of their duties was enormous. In addition to the traditional roles of caring for livestock and all that that entailed, and the production of grain and horticultural crops in greater quantities, there were specialist jobs, including thatching, and the felling of trees to offset timber lost once Norway became an occupied country. Despite reservations about their ability to drive tractors and operate ploughs, no task proved too difficult, although the harvesting of potatoes and sugar beet, and coping with huge amounts of dust coming from threshing machines, were particularly unpopular jobs.

To manage and support the land girls, there were influential Hampshire people who undertook the essential organisational responsibilities. Before a formal Committee was established, David Cowan, the county’s Director of Education, devised four-week training programmes first rolled out at Sparsholt’s Farm School in April 1915. He, with Mary Katherine “Kitty” Cook, who effectively exercised the challenging operation duties, formed the basis of the executive team. Hampshire’s War Agricultural Committee was led by Florence Baring, Countess of Northbrook, and she was joined by, among others, Laura Chute of the Vyne, Sherborne St John, and Pauline Woolmer White who was also a key figure during the Second World War. The duties in both wars included the selection and recruitment process, the welfare of land girls, controlling the financial costs, and the sourcing of sufficient residential accommodation.

Even though most land girls had no previous experience of farming, they became a well-regarded resource by the Government’s Ministry of Agriculture, the general public, and most farmers. A few, though, expressed contrary views; one Hampshire farmer said he would ‘rather give up his land than employ female labour’, and another claimed that ‘women were weak, or squeamish, or ill-disciplined, or empty headed.’ By the end of both world wars, however, messages of appreciation were a far more common response. Among many accolades, the editorial in the Land Girl of October 1950 told land girls that they ‘had obeyed the call of duty in the nation’s hour of great need, and Britain owed them an everlasting debt.’

I started this blog with a light-hearted family observation; I finish it with a sombre one for the nation to hear and act upon. The Women’s Land Army was formally demobilised on 30 November 1950. As the Second World War drew to a close, land girls were excluded from government grants and awards schemes that were designed to help women back to other occupations. The highly regarded Honorary Director of the Women’s Land Army, Lady Gertrude Denman, resigned in protest in February 1945, and objections were also expressed by MPs, farmers, and the Women’s Institute. In January 2008, the Independent expressed them thus;

‘…they were the women whose back-breaking labours in milking-parlours,

lumber yards and on muddy fields, helped to ensure that Britain did not

starve in the 2nd World War. While a grateful nation later saluted its

fighting forces, the 80,000 members of the Women’s Land Army (WLA)

received scant official recognition.’

That lack of “recognition” didn’t finish in 1945. Not until 2000 were former land girls invited to march past the Cenotaph on Remembrance Sunday, it was 2008 before the 20,000 or so land girl survivors received commemorative badges, and not until October 2014 was a memorial to the Women’s Land Army unveiled at the National Arboretum, Alrewas, Staffordshire. However, in November 2025, 75 years after the Women’s Land Army was disbanded, there will be the opportunity to pay special tribute to the 240,000 women and girls, many of them 17 and 18 years of age, who played vital roles in both world wars to satisfy Britain’s basic need for food. They performed hard, physical work, tirelessly, in all weathers, a long way from their homes, for 50 hours a week, with very little recreational time, and all for far less pay than female labour in other wartime situations. Let’s not overlook the chance to say with real sincerity; “We will Remember Them.”

Author: Dr John Lander

Bio: Having joined the staff of one of the major banks immediately after leaving school, John decided that when his youngest child left school and went to university, and he was no longer as committed to supporting him on the touch line of sports grounds or going through the Financial Tines with him almost each evening as he prepared for his A levels, he would undertake higher education study with The Open University. It was one of the best decisions of his life and he’s told many people since that the years during the study and after the award of a PhD in 2000 have been the most rewarding of his life. He’s been able to study and write about social history subjects that had long fascinated me, but just didn’t have the time to pursue as thoroughly as he wished. As a result he’s now written histories of several chapels, and researched the teetotal movement, especially as it affected Cornwall, where he lived for 18 years before we moved to Hampshire in 2019. In all there are now more than 30 books and papers written on a variety of 19th and 20th century history topics. This interest comes, in part, from having a keen social conscience which, among other appointments, has led him to chair two housing associations over the past 21 years, including Winchester Housing Trust Ltd., and undertake non-executive directorships on the Board of an NHS Hospital Trust and two further and higher education colleges, one in Cornwall and Sparsholt College. He’s also involved in a greatly appreciated church-based support group for Ukrainian families living in and around Winchester