The Mary Rose Museum in Portsmouth is world famous for its unrivalled maritime archaeology collection. The thousands of objects recovered from the wreck of Henry VIII’s warship offer a rare insight into life onboard a Tudor ship during battle— from the weapons to the personal possessions of the 500 strong crew, almost all of whom perished when the Mary Rose sank on 19th July 1545 during the Battle of the Solent.

However, what I’ve learned in my time as a Front of House Volunteer for the Museum over the last year, is how vital archives are to telling the story of this remarkable collection.

The unanswered questions

On one hand, we are limited in what we know about the sinking. For example, visitors are often curious to know the names of the people that went down with the ship. Sadly of the 500 men believed to be on board only one name is known for certain — the captain, Vice-Admiral George Carew.

Some visitors have heard the myth that the Mary Rose sank on her maiden voyage. Nothing could be further from the truth, but there are large gaps in our understanding of what happened on board, where she travelled, during her 34 years’ service.

Also, one of the biggest unanswered questions remains – “Why did the Mary Rose sink?”

Bringing the collection to life

Yet, there are some brilliant sources which – combined with the archaeology – reveal some fantastic stories.

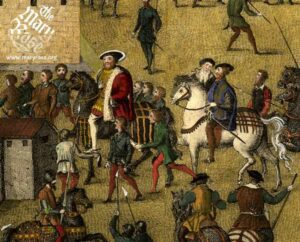

Most notably, the Cowdray Engraving. A copy of this dominates the 19th July 1545 Gallery at the museum. The original was a remarkably accurate contemporary painting for the walls of the house of Sir Anthony Browne, it captures the moment after the sinking of the Mary Rose mid-battle.

The original picture was lost when much of Cowdray House was destroyed during a fire in 1793. Thanks to engraved copies of the picture made in the early 1700s, we can show visitors a view as close as possible to that seen by Henry VIII and the people of Portsmouth at that tragic moment.

The Cowdray Engraving offers a unique window into life in Tudor Portsmouth. The Museum’s 19th July 1545 Gallery highlights several objects depicted in the engraving such as tankards, jerkins, halberds and guns. Remarkably, visitors can see the ship and many similar artefacts to the ones depicted within the engraving for themselves as they walk round the Museum.

Henry VIII, Anthony Browne and Charles Brandon from the Cowdray Engraving. Courtesy of Kester Keighley.

The Engraving includes many of the biggest names in Tudor England. Alongside Henry himself, the picture includes Anthony Browne, Charles Brandon, possibly the Queen Katherine Parr and the Imperial Ambassador Francois van der Delft.

Answering the biggest question: why did the Mary Rose sink?

Whilst we are unlikely to ever know for sure why the Mary Rose sank, the account of a Flemish survivor as told to the Imperial ambassador is one of the most plausible accounts. The Cowdray engraving shows van der Delft at Southsea Common that fateful day and it is through him that this dramatic account is recorded in a letter to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V.

He tells us that the ship, having fired the guns on one side, turned to fire from the other without closing the gun port lids. As the ship turned, she was caught by a sudden gust of wind which brought the open gun ports beneath the waterline causing the ship to capsize and sink. His words are quoted on the walls of the museum to try and explain to visitors why the pride of Henry VIII’s fleet should have sunk at such a pivotal moment.

There are other archival sources related to the sinking. One intriguing discovery was made in 2007 within the archives at Hatfield House. A torn sheet of paper was found of a report suggesting that a change requested by Henry, to move bronze guns as far forward as possible in his ships, would entail a “great weakening” of the Mary Rose. We do not know whether these works took place but if they had, could this have contributed to the sinking? You can see a copy of this document and read more about the mystery of the sinking in the new book published for the anniversary.

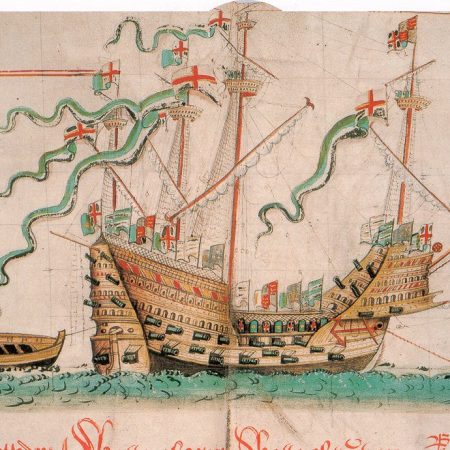

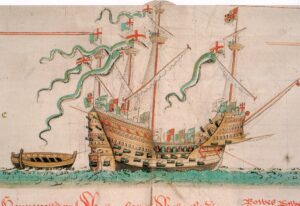

Alongside the Cowdray picture, archives also offer another image from a different source – the Anthony Roll. The only contemporary picture of the Mary Rose itself (the Cowdray picture only shows the tops of the mast, just after the moment of sinking). This is an illustration from an inventory prepared by Master of the King’s Ordnance Anthony Anthony. The roll is a remarkable document; one copy of which ended up in the personal collections of well-known seventeenth-century diarist Samuel Pepys and can be seen today at Magdalene College Cambridge.

Pepys Library , Magdalene College, Cambridge

Interestingly, the Roll was completed in the year 1546, a whole year after the Battle of the Solent so perhaps a little optimistic to include the Mary Rose within it. However, we know from archival sources – including Van der Delft’s account – that there were detailed plans to recover the wreck as soon as possible. Letters describe much of the sails, rigging and masts being laid out on Southsea seafront to dry in the months after the sinking. Again, this tallies with the archaeology; no trace of the masts or sails in use on the day of the battle were found when the ship was excavated during the twentieth century.

Delving deeper

I’ve still got a lot to learn about the Mary Rose – both her thousands of objects and what the archives tell us.

For the sixteenth century story, we have the fantastic Letters from the Mary Rose – recently re-published – compiled by C.S. Knighton and David Loades. It includes a wide array of original documents that tell the story of the life of the Mary Rose. This includes dispatches written aboard the ship by the commanders, records related to the ship’s construction and more presented in accessible language and with the relevant historical context.

This October the Mary Rose Trust is marking 40 years since the Mary Rose was raised from the seabed and brought back to the surface for the first time in 437 years. The broadcast in 1982 was seen by an audience of over 60 million around the world! As someone who wasn’t around to witness it, I’ve enjoyed the chance to learn more about the enormous efforts by the Mary Rose Trust, with volunteer divers from across Hampshire and further afield, to excavate and raise this remarkable wreck.

I’m as also keen to explore some of the objects in the Mary Rose Museum’s Secondary Collection which is a treasure trove in itself.

This still growing collection of objects related to the project aside from the Tudor artefacts. In this anniversary year, if you have something associated with the Mary Rose story that you would consider sharing, loaning, or even gifting, do please get in touch with the Mary Rose Trust and help it to continue to tell the story for future generations.

Author: Henry Rothery

Bio: I volunteer front of house at the Mary Rose a few Sundays a month – do say hello if you visit! The Mary Rose Museum is in Portsmouth Historic Dockyard and is open 7 days a week throughout the year. Plan a visit and step back in time to explore the world of Tudor England.