OMICRON may be remembered as something that was truly ‘horrible’, but it will probably be nothing compared to events in the past. These have probably given more entertainment to later generations than perhaps they should. Think 1066 and All That, Blackadder, and more recently Horrible Histories and Games of Thrones.

And then there is the Chesil Theatre’s parody 1093 And All That telling the tale of Winchester Cathedral’s 900th anniversary in 1993. Directed by Sue Hake, it was a group effort, with material written by a number of members, including Andrew Maliphant, Eira Parry-Jones, Lisbeth Rake, Gerry Tuff and Tom Williams.

In reality, the most popular horrible event was always a public hanging. Imagine the scene: a crowd of hundreds, even thousands is gathering, men are fussing around the scaffold, a noose hangs from the gibbet. A man (generally) is marched to the scaffold, accompanied by a priest. The hanging is carried out, with the ‘short drop’, which might take 20 minutes before the condemned person expires.

These gruesome scenes were set in places that held assizes for trying the most heinous of crimes, like Winchester, where Gallows Hill near the Jolly Farmer pub in the Andover Road marked the spot. After 1819, in response to public sensitivity, the place of execution was moved to the County Gaol in Jewry Street, with a scaffold erected over the main entrance in full view of the public.

Occasionally executions took place elsewhere – in Southampton, and even on Southsea Beach, and ‘in chains’ at Blockhouse Point and Hardway, both in Gosport, as well as at Portchester Castle.

Between 1735 and 1799 more than 700 death sentences were passed in the county, many of them commuted before the justices moved on to the next assize on the circuit, leaving about 160 that were not spared. These were for actions such as horse theft, housebreaking, ‘damaging a fishpond’, sheep theft, highway robbery and of course murder.

The last public execution in Winchester was that of Frederic Baker in 1867, whose murder of poor Fanny Adams has passed into the English language. The whole story has been told by Chris Heal in The Four Marks Murders. The hanging was carried out in the existing goal, on the Romsey Road, which dates from 1850. Thereafter, all hangings were carried out in private, the last in 1963.

In Tess of the d’Urbervilles Thomas Hardy has Tess hanged in Winchester Gaol, though no woman was ever hanged there.

As late as 1738 in Winchester there was a public burning at the stake, when Mary Groke aged 16 was executed for poisoning her mistress Justine Turner. On Saturday 18th March she was tied to a hurdle and dragged along to Gallows Hill. She apparently had to wait for two men to be hanged before being chained to a stake and surrounded by faggots.

Overall, for those who are interested in the past, raking over horrible events may be unseemly, but is probably a ‘good thing’. It hardly impugns a more serious pursuit of history and probably excite people’s interest in the subject and can raise some interesting questions, like, how authentic is Shakespeare’s depictions of the bishops of Winchester – Beaufort in Henry VI and Gardiner in Henry VIII? And in Game of Thrones how close is the Iron Throne of the Seven Kingdoms to the Saxon heptarchy during what used to be called the Dark Ages? Where might Essos be?

Even Jane Austen, who at the age of 15 wrote a ‘send up’ of her school history books, was less than serious. She questions whether Richard III really did kill his nephews, writing: “he was a York [and] I am inclined to suppose him a very respectable man”.

Children’s book writer Terry Deary has done a good deal for an interest in the past with such ‘horrible histories’ as Roman Tales, Tudor Tales, World War I Tales and many others. They have now been recast as a CBBC comedy series.

It took several versions to reach a mega-audience, starting in 2011 with the Gory Games series, followed by one fronted by Stephen Fry, in place of the puppet Rattus Rattus (presumably an improvement). The current series, which has won many awards, started in 2015.

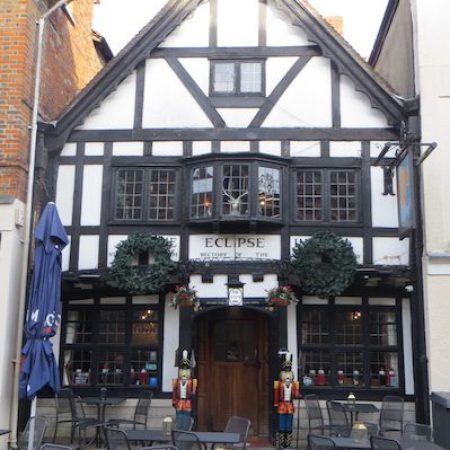

In 1685 a nasty piece of horrible history in Hampshire took place in The Square, Winchester, where buskers now entertain and the chattering classes take coffee. Here, on September 2, after a night in the Eclipse Inn, Dame Alice Lisle, wife of a parliamentarian, was publicly beheaded.

She was unfortunate enough to have been sentenced by Judge Jeffreys – who originally sentenced her to be burnt to death – at a time when the country was in a dark place. Within a few months of being crowned, ardent Catholic James II had had to stop the ham-fisted ‘pitchfork rebellion’ led by the Duke of Monmouth.

He was an illegitimate son of Charles II, who had himself almost lost his life in the Rye House Plot, for which William Lord Russell of East Stratton was also beheaded. Alice Lisle died for giving shelter to a well-known nonconformist minister, who was a fugitive from the Battle of Sedgemoor.

There are two much earlier killings that are marked in Hampshire. Dead Man’s Plack in Harewood Forest, near Longparish, is a monument that commemorates the murder by King Edgar in 963 during a hunt of the nobleman Ethelwald. He had sent him to assess Elfrida, daughter of Ordgar, Earl of Devon, as a possible bride. But things had not gone to plan. As the story goes, Ethelwald fell for the girl himself and married her, telling Edgar that she was a vulgar lass not suitable for being queen.

Unfortunately, the monument has, so to speak, been demolished by local historian the late John Spaul, who in 2004 suggested that its position was a huge mistake fostered by local landowner Lt Col William Iremonger, who in 1825 had erected it in the wrong place.

On much sounder ground is the Rufus Stone in the New Forest, though even now more than 900 years later experts find it impossible to establish the facts. In a recent article in the HFC Newsletter Alec Samuels wrote: “Killing a king can be a dangerous proceeding for perpetrators, a ‘botched job’ bringing inevitable retribution. Trying to kill a king by shooting him with an arrow on a hunt seems to be a very risky and unlikely enterprise.”

The earlier death in the New Forest of William Rufus’s older brother, Richard, might raise suspicions of foul deeds, but in fact he died from an accident involving an overhanging branch. Although Sir Henry Tirel (or Tyrell) is often suspected of carrying out the deed – and indeed he did flee the country – the most likely suspect for such a plan is Rufus’s younger brother, the future Henry I, who eagerly took control of the Treasury in Winchester after his death.

Alec comments: “Henry was not a pleasant character. He had previously murdered a prisoner. He certainly had the inclination or motive to remove Rufus, and the opportunity to contrive the killing of Rufus on the hunt.” But in his article, he leaves final judgment to ‘the jury’.

From an article by Barry Shurlock first published in the Hampshire Chronicle.