THERE is a well-known saying that ‘journalism is the first rough draft of history’ though who coined the phrase is not entirely clear. In fact, tracking down the author is itself an exercise in historical research that uses quotes from newspapers!

The best guess is probably that of Jack Shafer writing in Slate Magazine, the online current affairs journal. He examines the widely held view that it was Philip L. Graham, publisher of the Washington Post, whose widow credits the phrase to a speech he gave in 1963 in London to an audience of overseas correspondents.

Digging deeper in the Washington Post Shafer finds that the same phrase without the word ‘rough’ was used in 1948, and Graham may not have been the original author.

Whoever coined the phrase – and is it really important? – the point is that making a true statement about past events is rarely easy and leafing through old newspapers is a valuable exercise. In fact, now that so many titles are digitised and searchable online, local history is being propelled into a new era.

It started in 2013, when the British Library moved most of its newspaper archive in Colindale, in the London borough of Barnet, to Boston Spa in Yorkshire and made agreements with commercial parties to put the material online. The result was the British Newspaper Archive: whereas previously historians had to work from hard copies in dusty offices, or microfilm in record offices, they could now search and download sources with their laptop.

This has brought about a true revolution in historical research, according to New Milton historian Nick Saunders, who recently gave a virtual presentation on researching newspapers in the pandemic-beating Hands-On Local History series run by the Hampshire Archives Trust and the Hampshire Field Club.

Outlining the value of newspaper reports, he said: “They are often the only historical source for a subject. They also give us some idea of how people were thinking at the time and lead into other areas of research. They often give a wealth of detail not available elsewhere. And reports of court cases or public meetings provide a record of what people actually said.”

Read as many accounts as possible and, where available, compare local and national coverage, he advised. Comments on a person’s character are useful, whilst language and rhetoric are pointers to contemporary attitudes. Accounts of elections reveal promises by local politicians and details of discussions and speeches that may not be found in official sources such as Hansard.

As with any source, newspaper reports need some understanding of how they originated. He cautioned: “Always ask why it was written, who wrote it – often the literate elite – and what was the bias or leaning of the paper and its owner. Remember also that there was censorship during wartime.

And there can be errors. One study of the coverage of the effects of the 1834 Poor Law Act by The Times and other papers showed that one-third were accurate, one-third were embellished and one-third untrue.”

He emphasised that much more than headline stories may be of interest to the historian, including editorials, advertisements, births, marriages and deaths, the sports page, the Court Circular and especially letters to the editor. A string of letters published in local papers in the mid-1870s gives a valuable insight into the state of the poor at the time in Southampton. They came from Richard Griffin, a poor law medical officer and a leading light in a national body, the Charity Organisation Society, founded in 1869.

Newspapers can be accessed online in various ways. Personal paid subscriptions to Findmypast or the British Newspaper Archive can be taken out for various periods or the sites may be available in local libraries and record offices.

A master lesson on BNA search functions was a key part of the talk, now posted on the YouTube channel of HFC (www.hantsfieldclub.org.uk). Basic measures include searching with different spellings of names of people and places and using contemporary language, such as ‘The Great War’, not ‘World War One’.

Exact phrases can be searched by using double inverted commas and more complex searches with the AND, OR, and NOT filters. Wildcards widen coverage (e.g India*, which also gets Indian and Indians). One key tip was “stay focused and try not to be side-tracked” by headlines outside the area of interest.

Once located, press reports can be downloaded and saved. To facilitate later research, Nick emphasised the importance of naming saved items with the title of the newspaper, its date, page and column numbers and a short description of the ‘cutting’.

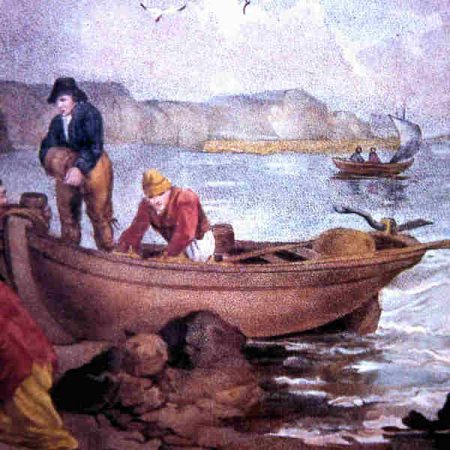

He demonstrated the enormous value of archived newspapers with a case of the killing of a smuggler on the New Milton coast by an ‘preventive officer’ based at Hurst Castle. It was sparked by research that found a bill sent to the parish by a local doctor in 1823. Intriguing items listed included “journey in the night…attendance on coroner…cutting for extracting ball…opening the body of James Read.”

A BNA search with the date of the bill led to accounts of the story in a number of local papers, including the Hampshire Chronicle, Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle, Southampton Town and County Herald, South Hants Chronicle and Hampshire Telegraph.

Accounts varied slightly, though the stages of the story were clear – from early reports, then the coroner’s court and then the crown court at Winchester. The Chronicle ran the story as “a severe and unfortunate contest … in Nash Field, near Chewton Bunny, about four miles east of Christchurch.” Later accounts gave the location as “Lob’s Hole”, which appears on a map surveyed in 1867.

The Chronicle reported that a local labourer James Read died “after several hours’ suffering” and an inquest was held at the Wheatsheaf Inn, Milton. A jury returned a verdict of “wilful murder” against HM Coastguards Lieutenant Pulling and William Young, only a year after the service had been set up.

It gave further detail: “A smuggling lugger made its appearance opposite Chewton Bunny, but the smugglers did not succeed in working their goods, and it was afterwards understood that the same were taken by a cutter.”

Other accounts reported 30-60 people on the beach, that Read was owed 30 shillings for seven nights’ work – when labourers were only paid about 9s a week – and one smuggler was found guilty by Southampton magistrates and committed to Winchester gaol.

At Winchester Assizes, William Young was cleared, though his commanding officer, Lieutenant Pulling, was found guilty of manslaughter. As reported in the press, the story then took a dramatic turn when after the trial a letter from a juryman surfaced, with instructions to witnesses on how to give evidence. As a result, Pulling was pardoned.

Commenting on the story, Nick said: “Researching the newspapers gave me a great deal of information about the incident – it gave me the location, the time, and it gave me about 10 names of locals that can be investigated further. It’s also given me an insight into the smuggling that was taking place at that time on the coast. And it’s given me the voices of some of the participants as heard in court.’

A final twist in the tale comes from the London Gazette of 1863, which shows that Pulling, then with the rank of captain, was promoted to rear-admiral, but “without increase of pay”. Naval records show that his long career involved extraordinary events at sea interspersed with quieter periods in the coastguard service. But that’s another story.

From an article by Barry Shurlock first published in the Hampshire Chronicle.