Bishops Waltham’s Debt to a Victorian Reformer and Social Entrepreneur

In the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, and the Metropolitan Museum, Fifth Avenue New York, are some rare terra-cotta objects from Hampshire dating from the 1860s.

They show scenes from the Odyssey and other classical tales. There are others in the collections of Bishop’s Waltham Museum and the Hampshire Cultural Trust. They make use of drawings of the sculptor John Flaxman (1755-1826) and are some of the finest products of their day.

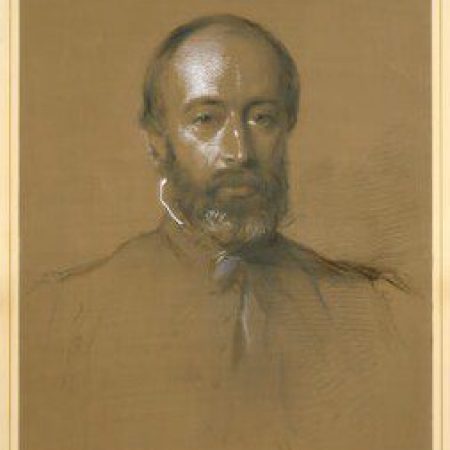

They were the brainchild of Arthur Helps (1813-1875), a social reformer and writer, who was knighted in 1871. His death in 1875 was noticed in newspapers from the north of Scotland to the Channel Isles. And yet none of them, including the Hampshire Telegraph, mentioned his attempts to rescue the small town of Bishops Waltham, when it was facing catastrophic unemployment.

Helps’ enterprises ended in financial ruin, but his life it could have been very different. The son of a wealthy London merchant, he was sent to Eton and went on to Trinity College, Cambridge. As a young graduate

he obtained patronage as a public servant of Prime Minister Melbourne. In 1841 the government fell and Helps with it. But the next year his father died, which gave him the means to buy the 3000-acre Vernon Hill Estate in Bishops Waltham. It took its name from Admiral Edward Vernon (1684-1759), known as ‘Old Grog’, who bought it with profits from a successful action aga

inst the Spanish during the War of Jenkins’s Ear (so called first by Carlyle!), an adjunct to the War of Austrian Succession.

Here Helps pursued a career as a writer of books on reform and social issues of the day. They often started with an essay, followed a vigorous fictitious discussion by a group of young men – Friends in Council, as one of his titles put it. He also wrote novels in a style that might now be called faction. The subjects included the evils of slavery and serfdom, the virtues and otherwise of emigration, the living conditions in cholera-prone towns, the errors and

sheer inhumanity – as he saw it – of the Spanish conquest of South America.

Helps was also active in the National Association for the Promotion of Social Science, which was way ahead of its time – it only lasted from 1857 to 1886. He also wrote biography, including the life of the civil engineering contractor Thomas Brassey (1805-1870), the man who built the London and Southampton Railway and much else.

His interests drew distinguished visitors to this corner of Hampshire, including the historian and social commentator Thomas Carlyle, the art critic John Ruskin and the Christian Socialist Charles Kingsley. His reputation at the time was so great that in 1860 he was offered the regius professorship of modern history at Cambridge, but declined (the job went to Kingsley).

But Helps did accept an appointment as Clerk of the Privy Council, which put him at the centre of power, with access to leading politicians and the royal family. Subsequently, he edited a collection of Queen Victoria’s letters, Leaves from a Journal of our Life in the Highlands (1868).

In the 1860s he turned his attention to his own locality. Here on his Vernon Hill estate he had found a deposit of fine clay: in fact, experts have described them as ‘some of the finest clay beds in the United Kingdom’. He took test borings and sent them off to Mark Blanchard, a London-based manufactu

rer of some of the best terra cotta products in the country. And the report was so good that in 1862 Helps decided to found the Bishops Waltham Clay Company. It was his attempt to bring business to a place that since the demise of the bishop’s palace had limped along with the ups and downs of farming.

The company initially made bricks and tiles, but in 1866 turned to making fine pots. He brought in people from Staffordshire and to reach the market in London and elsewhere he created with others a railway line between Bishops Walt

ham and Botley. It had a halt at Durley and provided links to Gosport and Portsmouth in one direction and Eastleigh and Southampton in the other. The Hampshire Telegraph of Saturday 6 June 1863 reported:

The Bishops Waltham Railway was opened for public traffic on Monday last, which made the little town full of bustle and life. The beautiful(ly) toned bells of the old parish church were ringing a merry peel the whole day, and a celebrated brass band paraded the town.

Helps also gave land to build the Royal Albert Infirmary at Newtown, Bishops Waltham, though it was never completed. The laying of the foundation stone in 1864 by a youthful Prince Leopold, the youngest son o

f Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, is the subject of a painting in the National Portrait Gallery .

After WWI the establishment became an English-speaking Catholic school, and then in about 1967 it became as a Police College. In the early 1990s it was demolished and the land developed for housing. An enduring legacy is The Priory Inn and a Catholic church, Our Lady Queen of Apostles. The full story is told by Peter Finn in History of the Priory, Bishops Waltham, 2002.

Helps was also active in creating create local utilities – routing mains water from Northbrook Springs, founding a gas and coke company, and introducing street lighting. He also built Abbey Mill, later owned by James Duke & Sons.

These were heady times: all seemed set

for Helps to show in practice what he had often advocated in his writings – it was pure Victorianism writ large! But by the middle of 1867 Helps had become financially overstretched and the production of the Bishops Waltham Clay Company ceased. Exacerbated by a banking crisis – and it w

as rumoured fraudulent agents – he was forced to sell the Vernon Hill Estate, which was described at the time as:

1300 acres consisting of gardens, pleasure grounds, shrubberies as well as several well-arranged farms and homesteads, productive water-meadows, cottages, fishing streams and capital shooting.

The unfinished Royal Albert Infirmary in Bishops Waltham was claimed by creditors. It became a private house, latterly called The Priory – though it never was a monastic establishment. However, in 1912 it did become a French-speaking Catholic school run by the White Fathers, missionaries from North Africa who had been expelled by the French state. They taught boys unable to study in a Catholic community in France.

An attempt was made at the time of the sale to claim back a statue of Prince Albert, presented by Sir Frederick Perkins

, ‘but the villagers objected strongly and a fray was fought which came to be called “The Battle of Bunker’s Hill” ’, according to the VCH. The full story is told in Peter Finn’s History of the Priory Bishops Waltham, 2002

It must have been a great disappointment to Helps when all his plans foundered. He was rescued by a grace and favour residence granted by the crown and for the rest of his life lived in Queen Charlotte’s Cottage, Kew, which had been built as a ‘rustic retreat’ by George III’s wife, Queen Charlotte (1744-1818).

Although the experience of financial ruin might have tempered his belief in Victorian values, he went on promoting social reform. His death when it came was greeted with an outpouring of gratitude and tributes. Today he is almost unknown, though in 2014 the scholar Dr Stephen Keck, in his

book Sir Arthur Helps and the Making of Victorianism argued that he should be put alongside all those reformers who improved the lot of so many people.

In fact, in Bishops Waltham, where he is remembered in the town’s delightful museum, his efforts eventually did pay off. A few years after the failure of his company, London brickmaker Mark Henry Blanchard took over the clay works and made a great success of it. In the opinion of one expert it ‘acquired a first-class reputation for its products, not just in the country, but in the whole world’. The nature of the deposit and ‘skilful firing’ made it ‘superior to other terra-cottas i

n point of hardness, texture, colour and finish’ (W.C.F. White, A gazetteer of brick and tile works in Hampshire, Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club, 1971, pp. 81-97).

For all these reasons, Blanchard bricks and terra-cotta ornaments were used in parts of Buckingham Palace, the Natural History Museum, and St Pancras Station. The company continued to make bricks until 1957. Its legacy is the Claylands Nature Reserve.

Bishops Waltham’s brush with the Industrial Revolution, therefore, gave it a source of employment for nearly a century. Also, its railway, now only marked by Old Station Roundabout and an oddly placed level-crossing gate (part of the the track is now a footpath), was an asset for agricultural merchants and others, especially during the strawberry growing season. It closed to passengers in 1933, but played a part in WWII and continued for freight until th

e axe of Dr Beeching fell in 1962.

A useful source is Newtown and Clay, 1860-1957: The story of pottery and brick production at Newtown, Bishops Waltham by Ted Pitman (Bishop’s Waltham Museum, 1977)