Charles I was born 423 years ago on 19th November 1600 in Dunfermline Castle, in Fife, Scotland. The second surviving son of James VI & I and Anna of Demark, Charles became heir after his older brother, Henry, died unexpectedly in 1612. Following James’ death in 1625 Charles inherited the thrones of Scotland, England, Ireland, and Wales, and soon married the French Princess, Henrietta Maria.

In my last blog for the Hampshire Archive Trust, I discussed the connections between the coronations of England’s three King Charles’ examining the material culture that binds these events together. In this instalment, and for Charles I’s birthday, I’ll be highlighting some fascinating places in Hampshire connected to the king and his family. These sites saw an assassination, celebrations, civil war, and the king’s own imprisonment, which eventually lead to his unprecedented execution in 1649.

Portsmouth:

Charles inherited not only the throne from his father, but also a close friend and advisor in the form of George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham.

Whilst the romantic and/or sexual nature of James and Buckingham’s relationship is widely debated, Buckingham can be seen to have altered his persona to better appeal to Charles’ tastes and sensitivities as James’ death drew near. Their friendship and Buckingham’s support of Charles whilst he was prince was demonstrated when they travelled together to Madrid in pursuit of a royal bride for Charles. Although the marriage negotiations did not end well the trip did influence Charles’ later artistic patronage and cemented his and Buckingham’s friendship. Paul M Hunneyball argues that “once [in Madrid] Buckingham adopted a flamboyantly heterosexual image and acquired a reputation for womanizing” which was a stark contrast to his previous effeminate persona that he had previously cultivated under James’ patronage.[1]

When Charles married Henrietta Maria in 1625 their relationship started badly, and Buckingham was part of the problem. The new queen consort’s Catholicism existed in stark contrast to England’s Protestantism. Henrietta Maria’s religion was protected by her marriage contract and thus she brought French attendants, including Catholic priests, with her to England which caused significant issues. Desperate to maintain his position, Buckingham drove a wedge between the newly married couple.

Buckingham’s powerful position angered many and in 1628 he was assassinated at the Greyhound Inn in Portsmouth by John Felton. A plaque now marks the spot where this happened, and the inn is now a hotel which celebrates its famous connection.[2] Felton insisted that he acted alone but it was three months before he was executed as officials were convinced he must have been part of a larger conspiracy. After his execution at Tyburn in London his body was taken back to Portsmouth where he was strung up and left to rot.[3]

Ye Spotted Dogge – the hotel that now occupies the building that was once the Greyhound Inn. Although it was be renovated and refronted the plaque by the door commemorates the event.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Buckingham_House,_Portsmouth-geograph.org.uk-4437606.jpg

Winchester Cathedral:

Buckingham’s death left Charles grieving the loss of his closest friend, and this is seen as moment of great change in Charles and Henrietta Maria’s personal relationship. The couple became incredibly close and are seen as having shared a mutual bond of love for the rest of their lives.

But did you know that the celling decorations at Winchester Cathedral celebrate the royal marriage and the strength of the Stuart dynasty? If you go into the cathedral, walk up the nave, through to the choir and look up you’ll see a set of carved decorations called ceiling bosses. One of these depicts the faces of Charles I and Henrietta Maria and another intertwines their initials ‘CMR’. But why the M? When Henrietta Maria and Charles were married in proxy before she came to England the English struggled to know what to call their new queen, and, in a bid to make her sound more English she was instead referred to as Queen Mary. Henrietta Maria never used the name herself, but its inclusion in the boss at Winchester Cathedral shows that the usage was widespread over a variety of mediums.

The ceiling redecoration was installed in 1634 as part of “a more ritual approach to worship, as encouraged by Charles I and Archbishop Laud” which led to the beautification of the area around the high altar.[4] Whilst other aspects of this decoration were later removed or destroyed during the civil wars some of these, including several wooden statues, can now be seen in the Kings and Scribes exhibition at Winchester Cathedral. Thanks to their height however the bosses were safe and can still be seen in situ today.

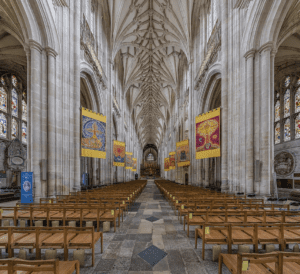

A view of the nave at Winchester Cathedral looking towards the choir.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Winchester_Cathedral_Nave_1,_Hampshire,_UK_-_Diliff.jpg

Carisbrooke Castle:

One of Charles I’s claims to fame is that he was the only king in English history to be publicly executed. Charles’ execution in 1649 took place outside of the Banqueting House in London, then a part of Whitehall Palace. The Banqueting House, with its impressive Peter Paul Rubens ceiling – that you can still see today – was a symbol of royal Stuart authority, power, wealth, and artistic patronage. In this way executing Charles at this site was highly significant, he even had to walk under the Rubens ceiling, with his father gazing down at him, to go to his execution.

Charles I’s execution outside of the Banqueting House in 1649.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_execution_of_King_Charles_I_from_NPG.jpg

Charles’ execution took place after conflict and civil war had erupted across Scotland, England, Ireland, and Wales from 1639. Hampshire played an important part in Charles’ civil war narrative and in the lead up to his execution, with Carisbrooke Castle and Hurst Castle both acting as prisons for the king. Having escaped from Hampton Court, where he had been held under house arrest, Charles arrived at Carisbrooke in 1647, hoping that he would have greater freedom and be able to gain support from the Governor of the Isle of Wight and the local people. At this point his execution was in no way expected and so Charles attempted to negotiate from his new position.

At the beginning Charles’ stay at Carisbrooke was not too harsh, he was given the finest room at the castle, allowed to ride out into the town of Newport, and a bowling green was created for his entertainment. However, Charles’ discussions with Parliament were not going the way he planned, and in 1648 he twice attempted to escape. On the first of these attempts Charles tried to climb out of a window but got stuck in the bars, which he had been convinced he could pass through. He was spotted and had to retreat to his room. After this first escape attempt his prison was further secured and he was moved to a different bedroom.

Later in September 1648 he was taken to Newport for further negotiations and when these did not proceed, Charles was taken to London to await trail. His removal to London saw him temporarily held at Hurst Castle, also in Hampshire, where his imprisonment had none of the comforts that he had first experienced at Carisbrooke.

Carisbrooke Castle, near Newport on the Isle of Wight. The chapel behind the garden was restored in 1904 but is built on the site of the chapel that Charles would have worshipped in during his imprisonment.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Carisbrooke_Castle_2011,_25.jpg

After Charles’ execution two of the royal child, Elizabeth and Henry, were imprisoned at Carisbrooke. Elizabeth died not long after arriving and was buried at St Thomas’s church in Newport. Originally Elizabeth’s final resting place was only marked with her initials, but Queen Victoria later commissioned a white marble tomb in 1856.

Other places to visit in Hampshire:

Whilst Charles travelled all over England during his life and reign these sites in Hampshire mark some of the kings’ highest and lowest points. He also visited Titchfield Abbey, Winchester College, and Beaulieu Abbey, so there’s loads of places in Hampshire visit to get your seventeenth-century history fix!

Footnotes:

[1] Paul M. Hunneyball, ‘James I and the duke of Buckingham: love, power and betrayal,’ The History of Parliament: British Political, Social & Local History. Accessed 04 November 2023. https://thehistoryofparliament.wordpress.com/2019/02/21/james-i-and-the-duke-of-buckingham-love-power-and-betrayal/.

[2] Anon, ‘Ye Spotted Dogge.’ Accessed 04 November 2023. https://www.yespotteddogge.co.uk/.

[3] Anon, ‘The Buckingham Assassination (1628),’ Early Stuart Libels. Accessed 04 November 23. https://www.earlystuartlibels.net/htdocs/buckingham_assassination_section/P0.html.

[4] Label Text, The cycle of decoration and destruction, Winchester Cathedral, Winchester. Accessed 5 June 2021.

Suggested Reading:

Campbell Barnes, Margaret. Mary of Carisbrooke. (Naperville: Sourcebooks landmark, 2011). – A historical fiction novel exploring Charles’ imprisonment at Carisbrooke Castle from the perspective of Mary, an assistant laundress who tried to help him escape.

Matusiak, John. The Prisoner King: Charles I in Captivity. (Stroud: The History Press, 2017).

Moore, Amanda. ‘Beaulieu Abbey,’ Hampshire History. Accessed 04 November 2023. https://www.hampshire-history.com/beaulieu-abbey/.

Porter, Linda. Royal Renegades: The Children of Charles I and the English Civil Wars. (London: Macmillan 2016).

Whitaker, Katie. A Royal Passion: The Turbulent Marriage of Charles I and Henrietta Maria. (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2010).

Places to Visit:

Banqueting House, London. https://www.hrp.org.uk/banqueting-house/#gs.0iq1v1.

Beaulieu Abbey, Beaulieu. https://www.beaulieu.co.uk/attractions/beaulieu-abbey/.

Carisbrooke Castle, near Newport, Isle of Wight. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/carisbrooke-castle/things-to-do/.

Hurst Castle, Milford on Sea. https://www.hurstcastle.co.uk/.

Newport Minster (St Thomas’s Church), Newport, Isle of Wight. https://newportminster.org/.

Titchfield Abbey, Titchfield. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/titchfield-abbey/.

Winchester Cathedral, Winchester. https://www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk/.

Author: Amy Saunders

Bio: Amy Saunders has recently submitted her PhD in history at the University of Winchester. Her research explores how early modern English and Scottish monarchs are represented in heritage sites. Her current work focuses on James VI & I, Anna of Denmark, Charles I, Henrietta Maria, Charles II, and Catherine of Braganza, exploring themes including othering, gender, sexuality, religion, parenthood, and conflict.

You can explore Amy’s research further via her LinkTree page which contains a variety of freely available blogs, podcasts, recorded public talks, and open access publications exploring royal studies, heritage reconstructions, and representations in popular culture.

For more history and heritage content you can follow her on X/Twitter @amyesaunders1 and on Instagram @amye_saunders.