To celebrate International Women’s Day, we take a look at the life and works of a brilliant but neglected women writer from Hampshire, the Victorian best-seller Charlotte Mary Yonge

When you think of nineteenth-century women writers with a Hampshire connection, Jane Austen is probably the name that comes into your mind. But Hampshire has a claim on another woman writer who was a major literary figure of her day: Charlotte Mary Yonge, who was born and lived all her life in the village of Otterbourne, outside Winchester. Although Yonge is not so well known today as Austen, she was a household name throughout the Victorian period, enjoying significant commercial and critical success. 2023 marks the bicentenary of her birth, and offers a welcome opportunity to celebrate the work of this versatile and unjustly neglected writer.

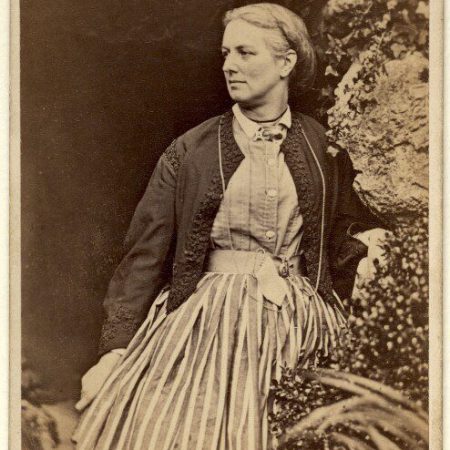

License: NPG 2193, © National Portrait Gallery, London. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs

Charlotte Yonge’s literary career was astonishingly long and prolific. She started young: her first novel (The Chateau de Melville) was privately printed to raise money for Otterbourne school when she was just fifteen, and her first novel with a commercial publisher (Abbeychurch) came out when she was twenty-one. She was still writing when she died in 1901, by which time she was the author of well over a hundred books, from biography and history to religious works, children’s books and even a famous history of Christian names. She wrote with such facility that she typically worked on three different things at the same time – something fictional, something factual, and something religious – writing a page of each in turn. But it was for her novels that she was best known.

Her breakthrough best-seller was The Heir of Redclyffe, published in 1853, which became one of the most talked-about novels of the day. The novel skilfully blends different generic traditions, marrying gothic menace with domestic realism to produce a distinctive and still highly enjoyable novel of rivalry, romance and moral redemption. In Yonge’s hands, what is essentially a family saga – the story of two cousins who inherit an ancient family feud and are in love with two sisters – becomes a Christian allegory, and also a vehicle for the medievalism that was in vogue at the time. Depicted as a kind of Victorian Sir Galahad, the hero Guy Morvillle is depicted as a throwback to an idealised chivalric past, and his feud with his mistrustful, prejudiced cousin Philip stages some of the most pressing intellectual and cultural conflicts of the day. It clearly struck a chord with contemporary readers. Admired by the future Prime Minister (William Gladstone) and the Poet Laureate (Alfred Tennyson), the novel appears to have been as popular with soldiers as with school girls, the favourite reading of officers in Crimea but also of Louisa M. Alcott’s Jo March in Little Women. Its sales speak for themselves: the novel went through five editions in its first year, and was still being reprinted almost annually by the end of the century.

After her signal success with The Heir, Yonge’s life outwardly changed very little. She continued to live with her parents in Otterbourne, teach at the village Sunday school, and – like Austen – she never married. But her life was only ‘uneventful’, as one biographer called it, from one point of view: her literary life was extremely busy, and notably successful. Although she had no pressing financial need to write – in fact she gave away most of the profits of her work, mainly to missionary and charitable work – she followed up The Heir of Redclyffe with a string of novels in a similar vein, melding convincing dialogue, nuanced characterisation, and intricate, slow-paced plotting with a distinctively High Anglican sensibility. Of her novels in the 1850s, Heartsease – which has interesting echoes of Austen’s Mansfield Park – Dynevor Terrace, and The Daisy Chain are notable successes, any one of which would justify her reputation as a major realist novelist. The last of these was particularly popular with younger readers, and gets a mention in numerous memoirs of Victorian girlhood, from Flora Thompson’s Lark Rise to Gwen Raverat’s Period Piece. Ethel May, the scapegrace teenage heroine, became one of Yonge’s most beloved characters, and Yonge re-introduced the lively May family in the sequel, The Trial, and in several of her later ‘family chronicles’. These loosely interlinked novels all have characters in common, so that the reader is given the sense of a whole fictional world. Although their length might make them a challenge for time-pressed readers today, Yonge’s gift for dialogue and her keen observation of family life – the tensions as well as the joys – still shine through. Those readers who can make time to work through the two volumes of her 1872 swansong The Pillars of the House are likely to find themselves thinking of the thirteen Underwood siblings as friends, as the novel follows them over sixteen years of their lives, tracing their successes and disappointments in an absorbing, expansive family saga.

If her novels are so readable, though, why did Yonge fall out of sight and largely out of print for much of the twentieth century? The answer is partly that critical fashions were unkind to her. Both too ‘feminine’ and perhaps too religious to find a place in the emerging canon of nineteenth-century novelists, she was also seen as too ‘conservative’ by many feminist critics when other Victorian women were being rediscovered. Her deeply religious outlook colours all her work, and was at odds with the increasingly secular wider culture.

Yonge was profoundly committed to High Anglicanism, specifically to the Oxford Movement (also called ‘Tractarianism’) which was emerged in the 1830s and 40s. She was very close friends with her parish priest, John Keble, a leading Tractarian who left Oxford to become Vicar of Hursley in 1836, and liked to think of herself as ‘a sort of instrument for popularizing Church views’. It is impossible to read and appreciate her novels without recognising their fundamentally religious underpinnings. Yet they are not full of explicit preaching; precisely because she was so heavily influenced by Keble, who believed in the value of ‘Reserve’, Yonge always preferred to work through symbolism, analogy, and allusion. In fact, her religious commitments clearly contributed to her development of a subtle realist style, whilst also informing her plotting at every turn. The worst thing that can befall characters in a Yonge novel is to lose their faith, and ‘self-sufficiency’ is not a virtue but a serious vice: characters have to recognise their ultimate dependence on others, and especially on the Church, in Yonge’s world view. This gives an interesting twist, though, to what would now be called her gender politics, because it leads her to fundamentally similar demands of her male and female characters. Her preference for tradition over innovation, and her distrust of any kind of secular personal ambition, made Yonge very sceptical of contemporary campaigns for women’s rights. However, her apparent conservativism on what was then called ‘the woman question’ is complicated by her keen interest in women’s domestic lives and her insistence on the worth of work conventionally gendered feminine; to read a Yonge novel is to enter a world in which women’s experiences count, and are often more centrally depicted than men’s.

Yonge’s politics generally defy easy translation into modern categories. It’s no wonder that her work was admired by William Morris, disciple of Ruskin and eventually Marx, as well as by Charles Kingsley the Christian Socialist. Her politics might best be described as Tory Radical – as much out of her step with the prevailing trends of her own period as of ours. She mistrusted what she saw as the utilitarianism and rationalism of the modern age, and was a passionate partisan for the Cavaliers against the Roundheads and the Established Church against dissent. She was indignant about the sufferings of the poor: her most idealised clergymen often give up brilliant careers to go and minister to slum parishes, and her aristocratic heroes consistently invite the scorn of their peers by caring more about their tenants’ welfare than about money-making. In some respects, her hyper-conservatism has aged rather well: she was distrustful of imperial adventuring when it was motivated, as she saw it, by money-grubbing and greed; her devout Christianity made her an enthusiast for missionary work, but also made her sceptical about white supremacy or European exceptionalism, since she took seriously the idea that all were made one in Christ.

Although in her later life Yonge tended to cast herself as something of a reactionary throwback, she actually kept pace with the times to an impressive degree, in certain respects. As the editor of The Monthly Packet – a High Anglican periodical which she ran for more than forty years – she encouraged and mentored many younger women writers, including the future best-seller Mary Ward, author of Robert Elsmere. She also came round to the idea of secondary and higher education for women – indeed, her friends arranged for two scholarships at Winchester Girls’ High School (now St Swithin’s) to be endowed with her name – and her later fiction suggests increasing openness to the idea of women pursuing careers. The obituaries written after her death in 1901 tended to characterise her as a reassuring, old-fashioned figure, but I think this is a serious underestimation of both the woman and the work. Yonge’s fiction has stood the test of time, and still has the capacity not only to entertain but to surprise and challenge its readers.

If you would like to discover more about Charlotte Yonge’s life and work, you can learn more on the web pages of the Charlotte M Yonge Fellowship, and read about their programme of events to celebrate Yonge in her bicentenary year: https://charlottemyonge.org.uk/

You can also hear Clare Walker Gore speaking about Yonge’s best-selling novel The Heir of Redclyffe on Radio 3 here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m001hnq7

Author: Dr Clare Walker Gore

Bio: Clare Walker Gore is a Lecturer in English at the Open University. She is the author of Plotting Disability in the Nineteenth-Century Novel (Edinburgh University Press, 2019), and co-editor of Charlotte Mary Yonge: Writing the Victorian Age (Palgrave Macmillan, 2022)