Amateur filmmaking, you might be surprised to know, has been characterised by some scholars as a “feminized cultural practice.”

Why, you ask?

Well, it all comes down to how cine cameras were marketed in the first half of the twentieth century and the perceived location of production – often within the private sphere of the home. Despite this gendered characterisation, women amateur filmmakers tend to be in the minority within extant film collections. Or at least, they are not immediately apparent in such collections.

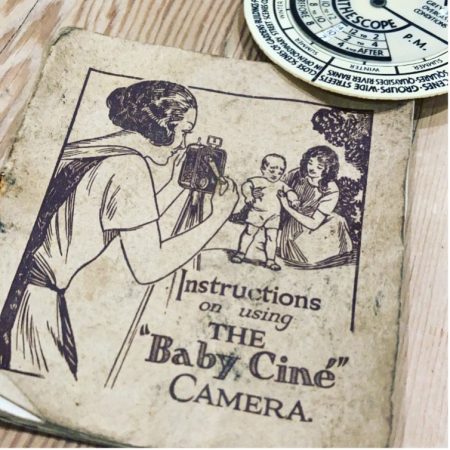

1 The Pathé Baby Cine instruction manual 1924. Image author’s own.

My research working closely with the amateur film collection of WFSA demonstrates that women are present within the archive in far greater numbers than previously believed, and that cine-engaged women are likely to be found in many more archives if only we change our approach to identifying them. With a focus on work produced between 1895-1950, I have conducted a first of its kind collection survey that documents the gender and occupational background of an amateur filmmaking populace. This innovative approach as allowed me to move away from a case study led discussion, towards consideration of filmmakers within a wider context, bringing in biographical details alongside re-examination of extant items to engage filmmakers and their work in critical discussion of amateur practice.

My findings indicate that as a result of entrenched patriarchal systems – we (and by we, I mean society at large) just don’t acknowledge women’s contributions to amateur film practice in the same way we do men’s. Even before films reach an archive, women’s role in the production of film is downplayed and minimised.

When families record their home movies, the films are often credited to the father or male spouse, even when close analysis of the on-screen footage shows that the male spouse appears on camera with the same frequency as the female partner. Who held the camera? Who shuffled children into view and tweaked the lighting? Filmmaking in these contexts was more often, collaborative than the sole work of one individual. However, the contributions of these women is considered not worthy of mention, the films were ‘his’ films, ‘his’ work and therefore when items are passed to an archive it becomes a matter of fact that the films are the product of a single male filmmaker. *

Cine clubs are another example where women’s roles have been found to be many and diverse – but as a result of reliance on terminology used by the professional film industry, many of the supporting functions within club settings (often carried out by women) don’t get mentioned in the film credits or in film write ups. My findings demonstrate that cine club members were at least 30% female, and that club memberships came from a far broader demographic that filmmakers working independently. Club membership was an affordable way for lower income participants to get involved.

In addition to the challenges women filmmakers encountered in how their work is discussed and acknowledged outside of the archive, there is also the challenge of how their contributions are described in the archive. In many cases there is little mention of gender within catalogue entries, and no way of identifying women’s work without a filmmaker’s name to search by. In my research I have discovered women in the collection referenced only in relation to their husband ‘wife of […]’, women whose names appear in credits without gender defining features (using initials only) and women who don’t get mentioned at all, even when there is a clear role sharing taking place between participants.

So what are the key findings from my work?

I am confident that using a more expansive methodology, as I have described above can shed light on women’s work – not necessarily to find new filmmakers, but to illustrate that women’s contribution to our shared amateur filmmaking experience is far greater than the present picture suggests – we just need to dig a little deeper.

*In some cases, yes, the male filmmaker did operate without help or assistance.

Author: Zoë Viney Burgess

Bio: Zoë is a final year PGR in film at the University of Southampton and also works as Film Curator at Wessex Film and Sound Archive in Winchester, UK and a Research Associate on the UKRI funded project at the University of East Anglia, Women in Focus. Her PhD research seeks to explore gender and class in the amateur film collection of Wessex Film and Sound Archive (WFSA) between the years of 1920-1950. At the University of Southampton Zoë has taught on the MA Film, MA Film and Cultural Management and on the MA Global Media Management. She has been involved in a number of UoS research projects including with the Social Practices Lab at Winchester School of Art and with the school of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics on the Investigating Incel Identity project. Zoë was the lead organiser for a major international conference in June 2022, hosted by the International Centre for Film Research celebrating the centenary of 9.5mm film, and is currently working on an anthology with Dr Annamaria Motrescu-Mayes on 9.5mm film.