In the final years of Elizabeth I’s reign, England had been plunged into a time of crisis following an undeclared war with Spain, the most powerful monarchy in Europe. Spain had assembled vast Armada’s for over a decade and threatened to invade England for the re-establishment of Catholicism after Elizabeth had restored the Church of England. This settlement led to ex-communication from the Pope, and frequent Catholic plots against Elizabeth’s rule. The people of England grew to fear violent Catholic repercussions many had witnessed during Mary I’s reign, and across Europe. [1]

In order to defend their home, Elizabeth relied upon a force of County Militia, involving conscription of every able man between the ages of sixteen and sixty who could wield a weapon. England had no professional standing army and the life-threatening demands imposed upon the Militia were extensive in order to reliably defend their home. The county Militia was organised by the Lieutenancy, led by the Lord-Lieutenants who were mostly Privy Councillors appointed for each county. Next in command were the Deputy-Lieutenants who led a lot of the groundwork for mustering and sending orders to the colonels, captains, and officers of the county divisions. A permanent watch was upheld across the nation, who sat and watched the coasts in fear, hourly, awaiting the lighting of signal beacons when an enemy fleet was sighted. The postmen on horse and foot were at all times ready to send word to the local officials from all seven divisions of Hampshire.[2]

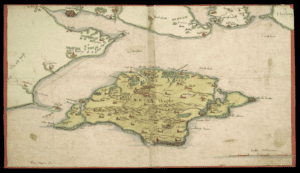

Hampshire was an economically and geographically vital county at the forefront of planned invasion-landings. The enemy forces never actually fought on English soil. What Hampshire, and most of the southern counties witnessed in the year 1599, were anticlimactic false-alarms as a result of poor communication. Hampshire’s Militia were forced to muster and march to the coastline (including aid from the surrounding counties) three times in one month which substantially drained their economy through taxation for equipment, especially at a time of poor harvests and rising economic inflation.

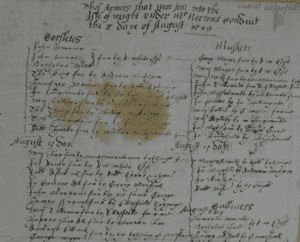

This research for Hampshire’s militia organisation relies heavily on Sir Richard Paulet’s military correspondence among the Jervoise Family of Herriard collection housed at the Hampshire Record Office.[3] Paulet was a captain over a Trained Band of militia within Basingstoke Division, and the documents show how far men from heavily agricultural parishes were pushed to meet the military demands placed upon them both at home and abroad. Additionally, the archive’s collection of a Deputy-Lieutenant letter-book provides the perspective from the Lieutenancy directly from the Queen and Privy Council, particularly from 1598 onwards.[4]

What is most evident from the correspondence is the increasing financial burdens faced by many military officials in command. We see the loss of position, and the threatened punishment of individuals by the Privy Council for absence or unpaid payments of equipment and supply. Sir Richard Paulet himself appears a very prominent figure in all of his sent letters, however, his later draft letters reveal serious financial difficulty and pleas for his status to remain intact. Altogether, the correspondence demonstrates how seriously Elizabeth’s regime took order to efficiently defend against the Spanish threat, including a rising sense of militant Protestantism with whom command was held.

Hampshire had a sketchy past in efficiently mustering for the repeated invasion threats. In 1591’s scare, out of 3000 men expected to aid the Solent at short-notice, 600 did not appear. During a surprise winter Armada in 1596, Lord Hunsdon as captain on the Isle of Wight was ready to take on the Spanish, yet claimed the soldiers on the mainland were ‘unable persons, ill-armed and unapparelled, and long a coming’.[5] There are no records of 1597’s scare in either of the collections for Hampshire, yet Lord Hunsdon told Robert Cecil that he “found the Hampshire bands in blissful ignorance of the Armada, having been so near the coast” (near Plymouth).[6] It was hoped that under the new Lieutenancy in 1599 the county had been given a chance to redeem their tarnished reputation.

The year began with a request for levies abroad to fend off the Irish rebellion, and warrants for the renewing of defective arms and equipment. On 25 July, the Privy Council advertised that a Spanish Armada was preparing to sail for England. The Militia were to prepare to rendezvous to the coast by 8 August. Richard Paulet’s muster rolls show that the Basingstoke division made the journey to the rendezvous location on time, however, this turned out this was a false alarm and nothing but a Dutch trading fleet passing the coast.

The first mustering of the entire county unimpressed the Deputy Lieutenant, and captain of Portsmouth, Hampden Paulet, as those appointed ‘made as slowe a repaire hither as I was earnest in calling them’. He continues in his wallowing displeasure to the Lord Lieutenant, placing the blame wholly on the Militia divisions, stating: ‘I am sorry and ashamed to report unto your Lordship the backwardness of these parts of the County…’ and that if the Lord Lieutenant were present, they would have undoubtedly improved.[7] Hampden Paulet may have over-exaggerated the claims to give the Council justification to heighten the demands on Hampshire’s divisions as he even claimed Southsea Castle had neither captains nor commander.[8]

On 11 August, the Council advertised that a Spanish fleet had been sighted off the coast of Brittany. Hampden Paulet sent out a long letter demonstrating his desire for an improved response upon the next alarm with further reinforcement for Portsmouth. In this warrant, the death sentence was reinforced upon every single role instructed, amounting to seven uses in this letter alone.[9] That same day, Sir Richard Paulet was promoted to colonel of Basingstoke Division, allowing him to muster their Militia. Paulet’s muster records show that the Militia did achieve its goal this time in mustering efficiently as his company had traversed south from the North of Hampshire to Hurst Castle, to ferry across and march to St. Helen’s on the Isle of Wight by 15 August. The Lieutenancy struggled for news of the Spanish fleet, some French trade ships passing by had no sightings, yet others had news of a fleet of “120 sayle of Spaniardes and 40 galleys”. A French barque which had passed along to Rye from the Groyne had sighted 12 galleons with ‘great numbers of Soldiers’, however plague had sent them back to Lisbon before the county militia were needed.[10]

By 18 August, the men on the Isle of Wight and at Portsmouth were discharged again. The Lieutenancy commented more positively ‘in respecte of the greate charge they have been att’. Hampden Paulet’s impression seemed a little more forgiving for the county at last ‘not doubting but they will be in a good reddines, as any other partes of the Shire, for theire repayre hither upon any suddaine alarm’.[11]

Although, just one week later, the forces were recalled to the coast for a third time. The Deputies organised the forces, this time encouraging the militia with the Queen’s pay instead of parish taxation in hopes they would be induced to more willingly make the expedition. The Lord-Lieutenant Hunsdon added: ‘soe hoping this news shall not displease you and give contentment to the Country’, understanding the frustrations from within the ranks of the soldiers.[12] This was another false alarm, which happened to be a Flemish fleet returning from the Canaries. Richard Paulet had begun mustering his men hours before he had received follow-up letters recalling the troops within the same day. The correspondence for the year 1599 finishes with payment owed before returning to Autumn musters, and back to the coastal watch.

Lindsay Boynton made the point that by the end of 1599 ‘no one could now jibe at Hampshire men for moving at a snail’s pace… their swiftness was exemplary’.[13] This is only a glimpse into the emergency, fears and panic in which the people of Hampshire, and of England, faced at home in 1599.

Generally, the Elizabethan regime stood up to the strains of the war effort surprisingly well. Hampshire committed to troop levies and local officials eventually paid for the equipment of the soldiers enrolled, with seemingly endless debts for supply and conduct noted up to the year 1603 in the correspondence. Altogether, what is vital about the Summer of 1599 is that the Lieutenancy did in fact achieve commitment, persistence and compliance of the orders they placed on the Militia in each of the alarms that were raised. If a Spanish army had landed, there would have been a significant challenge to face the Solent’s natural and man-made defences, alongside the vast numbers of incoming trained armies from the rest of the Kingdom. Past historians appear to hold a negative perspective on the Elizabethan Militia – yet they held an achievement in defensive organisation and they evidently improvement upon this at a time of national threat and dire economic circumstances.

[1] J. Harper, ‘“At their Uttermost Perils”: The Urgent Preparation of the Elizabethan Militia amidst the 1599 Spanish Armada Crisis in Hampshire, from the Perspective of Sir Richard Paulet and the Lieutenancy’, Southern History (43, 2023), p. 50-84.

[2] Hampshire’s Divisions included: New Forest, Kingsclere, Basingstoke, Andover, Alton, Fawley, Portsdown. Including the cities of Winchester and Southampton.

[3] Hampshire Record Office, Winchester, 44M69/G5/20/1-98, Jervoise, ‘military papers, mainly muster books, rolls and correspondence re Hampshire, 1587-1640s’.

[4] HRO, 5M50, ‘Volume entitled “Southton Marshal Busines”, being a letter and memorandum book of the Deputy Lieutenants concerning military affairs and the defence of the county’ – (For reference here I have numbered each letter in the order they appear on Microfilm, there is no numbered division of the letters on record at this time).

[5] Boynton, Elizabethan Militia, p. 194.

[6] Ibid., p. 197.

[7] H.R.O. 5M50/23.

[8] H.R.O. 5M50/23

[9] H.R.O. 5M50/29, 30, 31.

[10] H.R.O. 5M50/28, 31, 32; H.R.O. Jervoise, 44M69/G5/20/50.

[11] H.R.O. 5M50/32.

[12] H.R.O. 5M50/34, 35.

[13] Boynton, Elizabethan Militia (Abingdon: Routledge, 1971), p. 204.

Bibliography

Hampshire Record Office, Jervoise Family of Herriard, 44M69/G5/20/1-98, ‘military papers, mainly muster books, rolls and correspondence re Hampshire’, 1587-1640s.

Hampshire Record Office,5M50, ‘Volume entitled “Southton Marshal Busines”, being a letter and memorandum book of the Deputy Lieutenants concerning military affairs and the defence of the county’, 1588-1628.

Boynton, L., The Elizabethan Militia: 1558-1638 (Abingdon: Routledge, 1971).

Cruickshank, C. G., Elizabeth’s Army (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966).

J. Harper, ‘“At their Uttermost Perils”: The Urgent Preparation of the Elizabethan Militia amidst the 1599 Spanish Armada Crisis in Hampshire, from the Perspective of Sir Richard Paulet and the Lieutenancy’, Southern History (43, 2023), p. 50-84.

Author: Josh Harper

Bio: Joshua Harper gained his Masters Degree at the University of Winchester in 2020 specialising in the history of Tudor defence procedures and demands imposed upon Elizabeth I’s Militia during the Armada years’ 1587-1603. Hampshire Tudor defence research has been of interest for over 6 years, correlating with Josh’s current employment at the Mary Rose Museum in Portsmouth. With his recent publication in the Southern History Journal on the Elizabethan Militia in Hampshire, Josh is determined to reassess the traditionally negative picture attributed to Elizabeth’s Army in past historiography.