I was incredibly excited as it was my first trip to see the archival documents held at The National Archives (TNA). I had journeyed up from Hampshire by train; caught the tube to Kew Gardens and walked to the archives. Already having a Readers card, I had pre-ordered my documents and I had – thankfully! – managed to get through all the security checks. I have always been interested in the history of healthcare and a change of careers had taken me into the heritage sector and the Mary Rose Museum. So, there I was, finally getting to look at the actual documents listing the surgeons who were assigned to Henry VIII’s army-by-sea in 1513.

A large, buff coloured box was handed to me, and I carried it carefully to my desk. With bated breath I opened it up to find a wad of parchment a couple of inches thick and the size of A5 paper. On it were thousands of sixteenth century words and figures, ink splodges and personal marks. But my heart sank, the writing was illegible; the scribbles looked like spider scrawl and for the first time I considered I might have ‘bitten off more than I could chew’. I knew I needed help if I was going to succeed in understanding these documents.

That’s when I first signed up for a palaeography (the study of old handwriting) course run by Hampshire Record Office (HRO). The course, run by a senior archivist, covered some of the common peculiarities in spelling, punctuation, minims (vertical strokes in the letters i, m, n, u and v), difficult letters and abbreviations. Together with a small group of participants, we examined copies of sixteenth, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century documents and practised transcription (copying the text using modern letters). Guided by our archival expert we worked slowly through the documents, each taking turns and helping each other when we were baffled by a word. HRO have several different courses on offer, examining parish records, wills, probate inventories and manorial records and I have taken them all. And it is due, in no small part, to HRO that I have been able to commence a lifelong dream of mine, which is to undertake a PhD exploring the healthcare practises used by people in Hampshire and Wiltshire between 1475-1575.

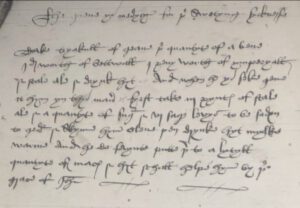

As part of my PhD, I have explored a range of records held at HRO. Recently, one of the documents I examined was a recipe for medicine treating sweating sickness (HRO 1M54/5 fol.148). Sweating sickness was an infectious disease that occurred in England between 1485 and 1551. There were five outbreaks during that time, and Dyer (1997) described the disease as being characterised by “sudden onset, profuse sweating, prostration and death or recovery within the space of twenty-four hours”. Although either sex could be infected, for young men it was generally fatal. This recipe was written in a parchment covered book, which had been the account book of William Norton, who was the Prior of Southwick Priory. The book belonged to Edward White, son of John White who came into possession of the priory after the Reformation. Consequently, the document has been dated as being written between 1511–1555.

Hampshire Record Office 1M54/5 fol.148. (Photo: Diane Budden)

Since taking the palaeography courses, I’ve developed my own way of working. Although I’m always tempted to dive straight in, I first scan the document to get familiar with the writing (hand) of the person (scribe) who wrote the piece. I look for easily identifiable letters, common abbreviations, and numbers. The person who wrote this recipe has strong writing, with nicely spaced letters and words. They have a flourished capital ‘T’ and use line fillers at the end of the recipe to prevent anyone adding anything else later. They also use ‘p’ which represents the sound ‘th’, therefore ‘pe’ is actually ‘the’. This is called a ‘thorn’, and it can look like a ‘y’. Many modern people think that people in the past used to pronounce ‘the’ as ‘ye’ (as in yeeha) but, actually, they just had different ways of writing the sound ‘th’.

Sixteenth-century spelling always makes me smile. At that time there was no systematic way of spelling so a writer may have used different ways of spelling the same word in the same document. This wasn’t seen as a weakness in those days. I’ve always been a poor speller and I recently found out I was dyslexic, but sometimes I think this is an advantage when transcribing sixteenth-century documents as I listen to the sound the letters make rather than thinking of the correct spelling. Mind you, transcribing an incorrectly spelt word hundreds of times doesn’t help a poor speller such as myself and I now find myself adding extra ‘e’s to everyday modern words.

Understanding a bit about the context in which a document was written or the subject that was written about also helps. Although physicians, surgeons and apothecaries did practise in the sixteenth century, for the majority of people healthcare was provided by the women of the household. Local people with knowledge of healing such as cunning folk could also be consulted. If a person was able to travel or could afford it, a cure from the apothecary or barber practising surgery could also be sought. Religion also continued to play a crucial role in the care of the sick persons’ soul. Indeed, people had no reservations about consulting more than one healer at the same time, be they offering natural or spiritual cures (Lindemann, 2010).

The Abbess, painting by Hans Holbein, depicting death. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

It is difficult to ascertain who wrote the recipe. Was it a member of the priory prior to its dissolution? Or was it a member of the White family, who had heard about the recipe from someone else and wrote it down? Unfortunately, the writing when compared with the other accounts and notes in the book does not match, so this is someone different. However, this recipe represents someone’s attempt to have a remedy available, should anyone they know be struck down with sweating sickness, a disease which would have, no doubt, caused fear and anxiety amongst the communities and families of Hampshire. As such it is a lovely example of sixteenth-century healthcare.

Whilst I am now quite skilled at palaeography, I would never describe myself as an expert. I am always learning from other people. No matter how many documents I have transcribed I always come across something that stops me in my tracks that I don’t recognise. Sometimes returning to the document later, with a fresh mind, makes the meaning clear, but sometimes another person may look at a word that I have been struggling with and immediately know what the writer meant. You must never be so self-absorbed that you can’t ask for a second opinion. However, with the help of HRO, I have been able to access sixteenth-century peoples’ thoughts and fears around sickness and disease and their plans and provision of healthcare. To be able to do that through their writing is a privilege and I will always be grateful for HRO’s help.

Dyer, Alan. ‘The English Sweating Sickness of 1551: An Epidemic Anatomized.’ Medical History, 41 (1997): 362-384.

Lindemann, Mary. Medicine and Society in Early Modern Europe. London: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Author: Diane Budden

Bio: Diane is a doctoral researcher in the Department of History at the University of Winchester. Diane’s thesis is a regional study which looks at the healthcare practices within, what Charles

Pythian-Adams described as, a cultural province. It compares and contrasts urban, rural and coastal

areas in parts of Hampshire and Wiltshire during the period 1475-1575. By doing so it considers the

impact of acts, statues and the Reformation on actual practise in a regional area rather than a large

urban area such as London. This compliments her recent employment the Mary Rose Trust and her

previous career in the NHS