An international business sparked by a Hampshire shepherd

A company that started in Hampshire and spread around the world has stepped up to lend its hand in the fight against the virus that has made a similar journey. It is retooling a trench coat factory to make non-surgical gowns and masks and donating substantial sums to charities and the search for a coronavirus vaccine being undertaken at the University of Oxford.

This is Burberry Group PLC, a company that can be traced back to 1856, when a young man who had been apprenticed to drapers John and James Angus in Horsham decided to get into business by buying a shop in Basingstoke. In an age of Victorian endeavour, the time was ripe for development and over the next half-century the town doubled its population.

Its big players were the firms of Burberry, Wallis and Steevens and Thornycroft. They brought extraordinary success to a North Hampshire town that had been industrially bereft since the loss of its cloth trade in about 1700. Of these, only the name of Burberry has survived. And the reason for this is undoubtedly the character of Thomas Burberry himself. (NB This source mistakes Winchester Street for Westminster Street).

He showed his genius by inventing a fabric that was weatherproof and breathable. This was ‘gabardine’, a registered the trade mark, subtly misspelt from ‘gaberdine’ which appears in Shakespeare and can be traced back to 1520. It was woven in Lancashire and made into specialist clothing in three different factories in Basingstoke. By 1871 Burberry was employing 80 hands. Over time, he created hundreds of jobs – mainly for women both from the town and further afield – and by all accounts he treated them very well.

The landmark Burberry products were all-weather clothing suitable for hunting, shooting and fishing – as well as workwear for the fields. There is a story – perhaps apocryphal – that he got the idea from talking to shepherds whose smocks were rendered weatherproof from handling sheep. Also, after an ‘argument’ with his local doctor he decided that the cloth should be breathable.

In modern parlance, Thomas Burberry was one of the first entrepreneurs to value the brand as highly, or even more so than the product. This, and a sense of the greater good, probably explains why he eased back from manufacture and sold two of his factories to people who had worked for him.

At the turn of the century, he and his sons took the business to London with help of an astute marketeer, R.B Rolls. Starting with a foothold in the Jermyns Street Hotel, Piccadilly (no longer there) they quickly established a presence and moved into flagship premises at 30 Haymarket. By 1914 they had branches in New York, Montevideo, Buenos Aires, and Paris.

The company gained approval at the highest level. Edward VII is credited with saying: ‘Give me my Burberry’ and gabardine clothing got huge publicity from explorers such as Shackleton, Scott, Amundsen and Nansen and the aviators Alcock and Brown.

What was to be huge stroke of good fortune came in 1901, when War Office asked the company to design a new service uniform for officers This led to the iconic trench coat – still a staple product – with half a million made during WWI alone.

Even as the company went from strength to strength, it seems, however, that Burberry was wary of being swept along and retained his retail business in Basingstoke. A directory entry of 1903 for the shops in Winchester Street and Church Street reads: “Burberry, T. & Sons Ltd, general drapers, outfitters tailors, house furnishers, china and glass dealers and undertakers”.

And a catastrophic fire of 1905 did not deter him from being a shopkeeper. On 17 April an attempt by milliner Miss Gray to ‘light up the front window’ of the Winchester Street shop with a taper went seriously wrong and the entire building was gutted. Despite the swift arrival of the local fire brigade, its steam-powered pump was unequal to the task. The situation was made worse by barrels of oil and cartridges stored nearby.

Today there are few signs that Thomas Burberry was ever in Basingstoke. His grave can be seen in South View Cemetery, and there is Goldings Park, which was secured as a WWI memorial by the family. But signs of the Strict Baptist faith that he held so dear have gone from Basingstoke, where he built a chapel, though at Hook stands the Life Church. This was built in 1957 on a part of site of his house, Crossways (the rest is a car park). It replaced the Mission Hall – formerly a Boer War officers’ hut – that he had erected in his garden.

Most records of the early years of the business were probably destroyed in the 1905 fire. The Burberry Group PLC has an archive, but it is not on open access. Also there are about 140 records in the HRO that demonstrate that Burberry was active in a large number of property deals, not all relating to his business needs. There are also packing instruction for clothing for Shackleton for Endurance and Aurora.

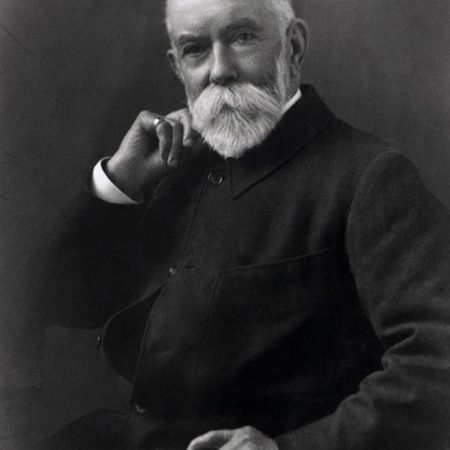

Only one photograph of Burberry seems to have survived and there are virtually no personal records. His obituary in the Hants & Berks Gazette (10 April 1926) refers to his ‘indomitable energy and a ‘vigorous constitution’ which he ‘attributes…partly to his abstemious mode of living…and…a rule of life which by most people would be regarded as singularly frugal’.

He was president of the Basingstoke Total Abstinence Society, and opened the Old Angel Café in the town to provide a meeting place without alcohol. In November 1881 he, and others, stood for municipal elections to counter townspeople who objected to anti-drink sentiments, as told in Bob Clarke’s The Basingstoke Riots (BAHSOC, 2010). But he and the other dissenter candidates lost to four members of the Conservative Party.

Someone who had worked for him for many years is quoted in his obituary as saying that he was a ‘kind and considerate master, not pampering anyone but rendering to each a just reward for faithful service’.

An exhibit on Burberry’s time in Hampshire can be seen in the Willis Museum and Sainsbury Gallery, Market Place. The full Burberry story is being researched by Dr John Hare and colleagues for the new Victoria County History. This major project to rewrite Hampshire’s history has already published ‘shorts’ on Medieval Basingstoke, Steventon, Cliddesden Hatch and Farleigh Wallop, with another on Penton Mewsey in press .

-

Thomas Burberry (1835-1926). Image: Burberry. -

Burberry’s shop, Winchester Street, Basingstoke, rebuilt after the 1905 fire -

Workroom, Burberry factory, Basingstoke -

Burberry ad for the trench-coat used in WWI. Image: Burberry. -

Logo once used by Burberry. Image: Basingstoke Heritage Society -

Mission Hut, Crossways, Hook. Image: Life Church, Hook